Languedoc & Roussillon

The Languedoc has a long history, complicated by the fact

that its name has changed several times, as have its borders,

sometimes radically. The region was settled by Celts,

with a Greek colony at what is now Marseille. It started taking

form under the Romans as their first province outside Italy,

Provincia

Gallia Narbonensis. In the fifth century as the Roman

Empire fell apart this province was ceded to the Visigoths

as Visigothic

Septimania (aka Gallia or Narbonensis). Due to Burgundian

incursions it shrank to become the Kingdom

of Narbonne and later expanded again as the Gothic

province of Gallia. In the eighth century it was over-run

by Moors and became Moorish

Septimania an outpost of al-Andalus. Later in the same

century it was again overrun, this time by the Franks, now

becoming Carolingian

Gothia. As Frankish influence waned, the area became identified

as the

County of Toulouse, an independent state, sharing a common

culture with a broader area known as Languedoc

or Occitania, both names preferring to Occitan, the common

language of the area. After it was annexed to France

in 1272, the County of Toulouse became a province of the Kingdom

of France. Known as the

Province of the Languedoc. After the revolution in 1789

the province of the Languedoc was divided into two, the eastern

part being having the Roussillon attached to it, and being

known as the Languedoc-Roussillon

region.

In summary the history is as follows:

Gaul. The area (corresponding roughly the modern

Languedoc and Provence) was part of Gaul occupied by Celts,

with a Greek colony at what is now Marseille.

More on the Languedoc in Celtic times

Provincia Gallia Narbonensis. The Romans founded

a colony (Provincia Gallia Narbonensis) in BC 123 covering

an area roughly corresponding to the modern Languedoc and

modern Provence.

More on Provincia

Gallia Narbonensis

Septimania. The western region of the Roman province

of Gallia Narbonensis passed under the control of the Visigoths

in 462 and was ceded to their king, Theodoric II. This area

was known as Septimania.

More on Visigothic

Septimania, Gallia, Narbonensis

Kingdom of Narbonne. As the area fragmented under

assaults from the King of Bugundy, the Goths established

a Kingdom of Narbonne.

More on the Kingdom

of Narbonne

Gothic province of Gallia. The area became a province

of the Visigothic Kingdom centred in Iberia.

More on the Gothic

province of Gallia

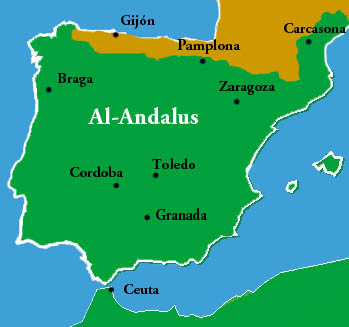

Moorish Septimania. The Moors, under Al-Samh ibn

Malik the governor-general of al-Andalus, sweeping up the

Iberian peninsula, by 719 overran Septimania.

More on Moorish

Septimania

Carolingian Gothia (8th century). When the Franks

overran the area they called it Gothia after the reign of

Charlemagne. , referring to the previous rulers.

More on Carolingian

Gothia

County of Toulouse. As Frankish power diminished,

a number of independent states were established in the area.

More on the .County

of Toulouse

Languedoc & Occitania. These terms were used

to denote an area with a distinct culture, stretching across

what is now southern France, of which the County of Toulouse

was the largest and central part.

More on Languedoc

& Occitania

The Province of the Languedoc. After it was annexed

to France in 1272, the County of Toulouse became a province

of the Kingdom of France.

More on The

Province of the Languedoc

The Languedoc-Roussillon. After the revolution in

1789 the province of the Languedoc was divided into two,

the eastern part being having the Roussillon attached to

it, and being known as the The Languedoc-Roussillon.

More on the Languedoc-Roussillon

region

Gaul

Before the Romans arrived, the area was part of Gaul, occupied

by Celts, with a Greek colony at what is now Marseille from

around 600 BC, and Phoenician settlements from 560 BC

More on Celts

in the Languedoc

More on Greek

settlement in the Languedoc

More on Phoenician

settlements

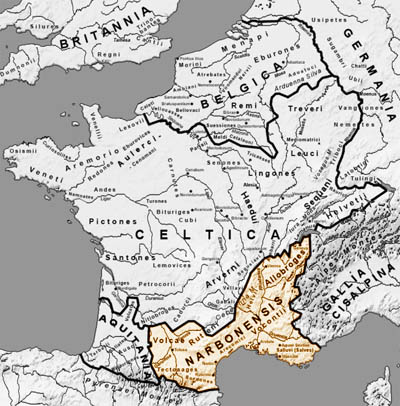

Gallia Narbonensis

The

Provincia Gallia Narbonensis was a Province of the Roman

Empire dating from 123 BC up until the 5th century. It was

originally known as Gallia Transalpina (Transalpine Gaul),

and informally by the Romans as as Provincia Nostra. The

Provincia Gallia Narbonensis was a Province of the Roman

Empire dating from 123 BC up until the 5th century. It was

originally known as Gallia Transalpina (Transalpine Gaul),

and informally by the Romans as as Provincia Nostra.

Gallia Narbonensis or in English Narbonese Gaul, named

from the settlement at Narbonne,

was the part of Gaul lying across the Alps from Italia.

Its western region was known as Septimania.

Gallia Narbonensis became a Roman province in the late

2nd century BCE, constituting the first significant Roman

territory outside of Italy. Its boundaries were roughly

defined by the Mediterranean

Sea to the south and the Cévennes and Alps and

north and west.

The province of Gallia Transalpina (Transalpine Gaul) was

renamed Gallia Narbonensis, after its capital the Roman

colony of Narbo Martius (Narbonne,

founded on the coast in 118 BCE.

Romans called it Provincia Nostra ("our province")

or simply Provincia ("the province"), as it was

the first significant permanent conquest outside the Italian

peninsula. The name has survived in the modern French name

of Provence, now a région of France, corresponding

to the Eastern part of Gallia Narbonensis.

History

Already

by the mid-2nd century BC, Rome had been trading heavily

with the Greek colony of Massalia (modern Marseille) on

the southern coast of Gaul. Massalia, founded by colonists

from Phocaea, was by this time already centuries old and

very prosperous. Rome entered into an alliance with Massalia,

by which it agreed to protect the town from local Gauls

and other threats, in exchange for a small strip of land

that it wanted in order to build a road from Italy to Spain,

to assist in troop transport. The Massalians cared more

about economic prosperity than territorial integrity - they

had no interest in empire building. It was from this strip

that Transalpine Gaul was founded. On this strip of land

the Romans founded the town of Narbonne,

which was to become a major trading competitor with Massalia. Already

by the mid-2nd century BC, Rome had been trading heavily

with the Greek colony of Massalia (modern Marseille) on

the southern coast of Gaul. Massalia, founded by colonists

from Phocaea, was by this time already centuries old and

very prosperous. Rome entered into an alliance with Massalia,

by which it agreed to protect the town from local Gauls

and other threats, in exchange for a small strip of land

that it wanted in order to build a road from Italy to Spain,

to assist in troop transport. The Massalians cared more

about economic prosperity than territorial integrity - they

had no interest in empire building. It was from this strip

that Transalpine Gaul was founded. On this strip of land

the Romans founded the town of Narbonne,

which was to become a major trading competitor with Massalia.

The area became a Roman province in 121 BCE, originally

under the name of Gallia Transalpina (Transalpine Gaul).

This name distinguished it from Cisalpine Gaul, the part

of Gaul on the near side of the Alps to Rome.

Mediterranean

settlements on the coast were threatened by the powerful

Gallic tribes to the north, especially the tribes known

as the Arverni and the Allobroges. In 123 BCE, the Roman

general Quintus Fabius Maximus Allobrogicus campaigned in

the area and defeated the Allobroges and the Arverni under

king Bituitus. This defeat substantially weakened the Arverni

and ensured the security of Gallia Narbonensis. It was from

the capital of Narbonne

that Julius Caesar began his Gallic Wars.

Bordering Italy, control of the province provided the Roman

state with significant benefits, control of the land route

between Italy and the Iberian peninsula; a buffer against

attacks on Italy by tribes from Gaul; and control of the

lucrative trade routes of the Rhône

valley, over which commercial goods flowed between Gaul

and the trading centre of Massalia.

At one point, Narbonese Gaul and Transalpine Gaul were

governed as separate territories. When the Second Triumvirate

was formed, Lepidus was given responsibility for Narbonese

Gaul and Spain, while Mark Antony was given Cisalpine and

Transalpine Gaul.

More on the Romans

and Gallia Narbonensis

Septimania, Gallia, Narbonensis

Under

Theodoric II, Visigoths settled in Aquitaine as foederati

of the Western Roman Empire (450s). Visigoths were then

holding the Toulousain - the Area around Toulouse.

In 462 the Empire granted the Visigoths the western half

of the province of Gallia Narbonensis to settle. In fact

the Visigoths under King Theodoric II initially occupied

the whole Provence (including eastern Narbonensis) in 462,

but in 475 the Visigothic king, Euric, ceded the eastern

Narbonensis to the Roman Empire by a treaty under which

the emperor Julius Nepos recognised the Visigoths' full

independence in respect of their other territories. Under

Theodoric II, Visigoths settled in Aquitaine as foederati

of the Western Roman Empire (450s). Visigoths were then

holding the Toulousain - the Area around Toulouse.

In 462 the Empire granted the Visigoths the western half

of the province of Gallia Narbonensis to settle. In fact

the Visigoths under King Theodoric II initially occupied

the whole Provence (including eastern Narbonensis) in 462,

but in 475 the Visigothic king, Euric, ceded the eastern

Narbonensis to the Roman Empire by a treaty under which

the emperor Julius Nepos recognised the Visigoths' full

independence in respect of their other territories.

Septimania was the western region of the Roman province

of Gallia Narbonensis. Under the Visigoths it was known

as Gallia or as Narbonensis. It corresponded roughly with

the modern French region of Languedoc-Roussillon.

The name "Septimania" may derive from part of

the Roman name of the city of Béziers,

Colonia Julia Septimanorum Beaterrae, which in turn alludes

to the settlement of veterans of the Roman VII Legion in

the city. Another possible derivation of the name alludes

to the seven cities (civitates) of the territory: Béziers,

Elne,

Agde, Narbonne,

Lodève, Maguelonne, and Nîmes.

Septimania extended to a line half-way between the Mediterranean

Sea and the Garonne River in the northwest; in the east

the Rhône

separated it from Provence; and to the south its boundary

was formed by the Pyrenees.

More on Alamans,

Vandals and Visigoths and Septimania

Kingdom of Narbonne

As control of the area fragmented, the Visigoths maintained

a kingdom centred on Narbonne,

though they lost control of even their capital from time

to time.

The Visigoths, because they were Arian Christians, met

opposition from the Catholic Franks in Gaul. The Franks

allied with the Celtic Armorici, whose land was under threat

from the Goths south of the Loire, and in 507 Clovis I,

the Frankish king, invaded the Visigothic kingdom, whose

capital was Toulouse.

Clovis defeated the Visigoths at the Battle of Vouillé.

The Goths' child-king Amalaric was carried away to safety

in Iberia, while Gesalec was elected to replace him and

rule the remaining Visigothic kingdom from Narbonne.

Clovis, his son Theuderic I, and his Burgundian allies

proceeded to conquer most of Gothic Gaul, including the

Rouergue (507) and Toulouse

itself (508). The attempt to take Carcassonne, a heavily

fortified site guarding the Septimanian coast, was defeated

by the Ostrogoths (508) and Septimania thereafter remained

in Visigothic hands, though the Burgundians managed to take

and hold Narbonne

for a time and drive Gesalec into exile. Border warfare

between Gallo-Roman bishops and other powerful nobles against

the Visigoths had become common during the last phase of

the Empire and this warfare continued under the Franks.

Kings after Alaric II favoured Narbonne

as a capital, but twice (in 511 and 531) were forced back

to Barcelona by the Franks before Theudis moved the capital

there permanently.

The Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great reconquered Narbonne

from the Burgundians and re-established it as the provincial

capital. When Theodoric died in 526, Amalaric was elected

king in his own right and he immediately established his

capital in Narbonne.

He ceded Provence (which had again passed back into Visigothic

control) to the Ostrogothic king Athalaric.

The Frankish King of Paris, Childebert I, invaded Septimania

in 531 and chased Amalaric back over the Pyrenees

to Barcelona in response to pleas from his sister, Chrotilda,

who claimed that Amalaric (her husband) had been mistreating

her. The Franks did not try to hold the province, but raided

it again in 541.

Under Amalaric's successor the government of the kingdom

crossed the Pyrenees

, Theudis establishing his capital at Barcelona. Later the

capital of the Visigothic kingdom moved further south to

Toledo.

By the end of the reign of Leovigild, the province of Gallia

Narbonensis, usually shortened to just Gallia or Narbonensis

(and not now called Septimania) was both an administrative

province of the central royal government and an ecclesiastical

province whose metropolitan was the Archbishop of Narbonne.

The province of Gallia held a unique place in the Visigothic

kingdom, as it was the only province outside of Iberia,

north of the Pyrenees

, and bordering a strong foreign tribe, the Franks.

Under Theodoric Septimania had been safe from Frankish

assault. When Liuva I succeeded the throne in 568, Septimania

was a dangerous frontier province and Iberia was wracked

by revolts. Liuva granted Iberia to his son Leovigild and

kept Septimania to himself.

Gothic province of Gallia

During the revolt of Hermenegild (583-585) against his

own father Leovigild, Septimania was invaded by Guntram,

King of Burgundy, possibly in support of Hermenegild's revolt.

A Frankish attack in 585 was repulsed by Hermenegild's

brother Reccared, who was ruling Narbonensis as a sub-king.

Hermenegild died at Tarragona that year and Reccared took

Beaucaire

(Ugernum) on the Rhône

near Tarascon and Cabaret

(now called Lastours),

both of which then lay in Guntram's Burgundian kingdom.

Guntram ignored pleas for a peace in 586, so Reccared undertook

a Visigothic invasion of Francia.

Guntram invaded Septimania again in 589 and was roundly

defeated near Carcassonne

by Claudius, Duke of Lusitania. Throughout the sixth century

the Franks had coveted Septimania, but were unable to take

it. The invasion of 589 was their last attempt.

In the seventh century Gallia had its own governors or

duces (dukes), who were typically Visigoths. Most public

offices were also held by Goths, far out of proportion to

their part of the population who throughout all this were

descendants of the original Celts.

The native population of Gallia was referred to by Visigothic

and Iberian writers as "Gauls" and there is a

well-attested hatred between Goths and Gauls. Gauls commonly

insulted the Goths, though the Goths regarded themselves

as the defenders and protectors of the Gauls.

By the time of Wamba and Julian of Toledo a large Jewish

population had grown up in Septimania.

Thanks to the preserved canons of the Council of Narbonne

of 590, something is known about surviving pagan practices

in Visigothic Septimania. The Council may have been responding

in part to the orders of the Third Council of Toledo, which

found "the sacrilege of idolatry [to be] firmly implanted

throughout almost the whole of Iberia and Septimania. The

Roman pagan practice of not working Thursdays in honour

of Jupiter was still prevalent. The council set down penance

to be done for not working on Thursday (except for church

festivals) and commanded the practice of rest from rural

work on Sundays, to be adopted. The council also decreed

punishment for fortune-tellers, who were to be publicly

lashed before being sold into slavery.

Visigothic coinage did not circulate in Gaul outside of

Septimania and Frankish coinage did not circulate in Iberia

or Septimania, which suggests little cross border trade.

If there was a significant amount of commerce over the frontier,

the coins paid must have been melted down and re-minted.

Moorish Septimania

The

Moors, under Al-Samh ibn Malik the governor-general of al-Andalus,

swept up the Iberian peninsula, and by 719 had overrun Septimania.

Al-Andalus is also known as the Emirate of Córdoba. The

Moors, under Al-Samh ibn Malik the governor-general of al-Andalus,

swept up the Iberian peninsula, and by 719 had overrun Septimania.

Al-Andalus is also known as the Emirate of Córdoba.

Al-Samh set up his capital from 720 at Narbonne,

which the Moors called Arbuna, offering the still largely

Arian Christian inhabitants generous terms and quickly pacifying

the other cities. Following the conquest, al-Andalus was

divided into five administrative areas roughly corresponding

to Andalusia, Galicia and Lusitania, Castile and Léon,

Aragon

and Catalonia, and Septimania.

With Narbonne

and its port secure, Arab mariners were now masters of the

Western Mediterranean.

The Moors swiftly subdued the largely unresisting cities,

still controlled by their Visigoth counts: taking Alet

and Béziers,

Agde, Lodève, Maguelonne and Nîmes.

By 721 Al-Samh was reinforced and ready to lay siege to

Toulouse,

a possession that would open up Aquitaine to him. His plans

were overthrown in the disastrous Battle of Toulouse (721),

with immense losses, in which al-Samh was so seriously wounded

that he died soon afterwards at Narbonne.

Arab forces based in Narbonne

and easily resupplied by sea, struck eastwards in the 720s,

penetrating as far as Autun (725).

In 731, the Berber wali of Narbonne

and the region of Cerdagne, Uthman ibn Naissa, called "Munuza"

by the Franks, who was recently linked by marriage to duke

Eudes (or Odo) of Aquitaine, revolted against Córdoba,

and was defeated and killed.

In October of 732, an Arab force under Abdul Rahman Al

Ghafiqi encountered Charles Martel between Tours and Poitiers,

and was defeated. This "Battle of Tours" (also

called the Battle of Poitiers) is celebrated in popular

Christian history and traditionally credited with stopping

the Moorish advance in Europe.

More on the Moors

and al Andalus

Carolingian Gothia

Franks

had been expanding southward since the fifth century. By

the eighth century they were probing as far south as the

Visigothic Aquitaine and Toulousain, and Moorish Septimania. Franks

had been expanding southward since the fifth century. By

the eighth century they were probing as far south as the

Visigothic Aquitaine and Toulousain, and Moorish Septimania.

The territory round Toulouse

was taken by the Franks in 732 following the "Battle

of Tours". Pippin III then directed his attention to

Narbonne,

but the city held firm in 737, defended by Goths and Jews

as well as Moors under the command of its governor Yusuf,

'Abd er-Rahman's heir.

Around 747 the government of Septimania (and the Upper

Mark, from the Pyrenees

to the Ebro River) was given to Aumar ben Aumar.

In 752 the Gothic counts of Nîmes,

Melguelh, Agde and Béziers

refused allegiance to the Emir at Córdoba and declared

their loyalty to the Frankish king. These Gothic counts

along with Franks then began to besiege Narbonne.

Narbonne

resisted but attacks continued and Narbonne

capitulated in 759. The county was granted to Miló

who had previously been the count in Muslim times. The Roussillon

was then taken by the Franks in 760.

In 767, after fighting Waifred of Aquitaine, the Franks

took Albi,

Rouergue, Gévaudan, and the city of Toulouse.

The following year, in 777 the wali of Barcelona (Sulayman

al-Arabi), and the wali of Huesca (Abu Taur), and the wali

of Zaragoza. (Husayn), offered their submission to Charlemagne.

When Charlemagne invaded the Upper Mark in 778, Husayn

refused allegiance and he had to retire. In the Pyrenees

, the Basques defeated his forces in Roncesvalles (August

15, 778).

The Frankish king found Septimania and the borderlands

so devastated and depopulated by warfare, with the inhabitants

hiding in the mountains, that he made grants of land that

were some of the earliest identifiable Frankish fiefs to

Visigothic and other refugees. Charlemagne also founded

several monasteries in Septimania, which doubled as fortresses

around which the people gathered for protection.

Beyond Septimania to the south Charlemagne established

the Spanish Marches on the borderlands of his empire. The

territory passed to Louis, king in Aquitaine, but it was

in practice governed by Frankish margraves of Septimania,

later (from 817) the dukes of Septimania.

The Frankish noble Bernat of Gothia (aka Bernat of Septimania)

was the ruler of these lands from 826 to 832. His career

characterised the turbulent 9th century in Septimania. His

appointment as Count of Barcelona in 826 occasioned a general

uprising of the Catalan lords at this intrusion of Frankish

power. For suppressing Berenguer of Toulouse

and the Catalans, Louis the Pious rewarded Bernat with a

series of counties, which roughly delimit 9th century Septimania:

Narbonne,

Béziers,

Agde, Magalona, Nîmes

and Uzès.

Rising against Charles the Bald in 843, Bernard was apprehended

at Toulouse

and beheaded in 844.

By the end of the ninth century the Franks were calling

Septimania Gothia or the Gothic march (marca Gothica).

Septimania became known as Gothia after the reign of Charlemagne.

It retained these two names while it was ruled by the Counts

of Toulouse during early part of the Middle Ages, but

the southern part became more familiar as Roussillon

and the west became known as Foix, and the name "Gothia"

(along with the older name "Septimania") faded

away during the 10th century, except as a traditional designation

as the region fractured into smaller feudal entities, which

sometimes retained Carolingian titles, but lost their Carolingian

character, as the culture of Septimania evolved into the

culture of Languedoc.

The name was used because the area was populated by a higher

concentration of Goths than in surrounding regions. The

rulers of this area, when joined with several counties,

were titled the Marquesses of Gothia or the Dukes of Septimania.

More on the Franks

County of Toulouse

As a march of the Carolingian Empire, and then of West

Francia as the empire fractured, Septimania become increasingly

culturally and politically separate from France and its

central royal government. The region was heavily influenced

by the Toulousain, Provence, and Catalonia and was part

of the cultural and linguistic region sometimes called Occitania.

Although Occitania

was never ruled as a unified state it shared much in common

(language, food, architecture, culture, and so on). Much

of the area was ruled by the Dukes

of Aquitaine to the West and the Counts

of Toulouse to the East, both of whom played of the

neighbouring powers against each other, notably the Counts

of Barcelona (later Kings of Aragon),

the Kings

of England, the Kings

of France and the Holy Roman Emperor.

The Counts

of Toulouse (who were also Dukes of Narbonne)

also had to contend with other local powers, most notably

the Counts

of Carcassonne and Beziers , and later the Viscounts

of Carcassonne and Beziers, and Counts

of Foix.

Under the Ramondine Counts

of Toulouse the area knew its golden age. Rulers were

educated, tolerant and liberal. Jews

and other minorities enjoyed ordinary civil rights. Occitan

became the first post-classical literary language of Europe.

The culture of the Troubadours

was borne and flourished, as did a sophisticated world-view

characterised by "paratge".

Lay learning was encouraged, the extensive corruption of

the Church was widely ridiculed. Ridiculing the Church and

refusing to pay tithes had consequences. In the early thirteenth

century the area was devastated by a Holy

Crusade called by the Pope. The high culture of central

Occitania

was destroyed by French barbarian invaders and Church Inquisitors.

Later in the thirteenth century the area would be annexed

by France.

You can read about this tragedy by clicking here to open

a new page on the Cathar

Crusade.

Septimania had became known as Gothia after the reign of

Charlemagne. It retained these two names while it was ruled

by the Counts

of Toulouse during early part of the Middle Ages, but

the southern part became more familiar as Roussillon

and the west became known as Foix, and the name "Gothia"

along with the older name "Septimania" faded away

during the 10th century, except as a traditional designation

as the region fractured into smaller feudal entities, which

sometimes retained Carolingian titles, but lost their Carolingian

character, as the culture of Septimania evolved into the

culture of Languedoc.

More on The

Counts of Toulouse

Languedoc

The French referred to Septimania and to Occitania

as the Languedoc, the area where a distinct language was

spoken, a literary language derived from Latin, which at

the time was called Roman but is now called Occitan,

or by the name of one of its dialects, Provençal.

In 1272 the lands of the Counts

of Toulouse were annexed to France under the terms of

the Treaty of Meaux.

The term Languedoc originally referred to the Occitan

language - the language in which the word for "yes"

was "Oc". The Langue d'Oc was the "tong of

oc". Later the term was extended to area where Occitan

was spoken, and the word is still used in both ways today.

More on War

against the Cathars

More on The

Annexation of the Languedoc to France

The

Province of the Languedoc The

Province of the Languedoc

Under the Treaty of Meaux in 1229 the Languedoc (Occitan:

Lengadòc) became a Province of France. Its capital

city was Toulouse,

now in Midi-Pyrénées. It had an area of approximately

42,700 km² (16,490 sq. miles).

It comprised essentially eight of the modern French départments

in the current regions of Languedoc-Roussillon and Midi-Pyrénées

in the south of France

The traditional provinces of the kingdom of France were

not formally defined. A province was simply a territory

of common traditions and customs, but it had no political

organisation. Today, when people refer to the old provinces

of France, they actually refer to the "gouvernements"

as they existed in 1789.

Gouvernements were military regions established in the

middle of the 16th century whose territories matched those

of the traditional provinces. However, in some cases, small

provinces had been merged with a large one into a single

gouvernement, so gouvernements are not exactly the same

as the traditional provinces.

Historically, the Languedoc region was called the county

of Toulouse,

a county independent from the kings of France. The county

of Toulouse was made up of what would later be called Languedoc,

but it also included:

- the province of Agenais (now eastern half of the département

of Lot-et-Garonne) to the west of Languedoc,

- the province of Gévaudan (now département

of Lozère),

- the province of Velay (now the central and eastern part

of the département of Haute-Loire),

- the southern part of the province of Vivarais (now the

southern part of the département of Ardèche)

- the northern half of Provence.

After the French conquest the entire county was dismantled,

the central part of it being now called Languedoc.

The gouvernement of Languedoc was created in the middle of

the 16th century. In addition to Languedoc proper, it also

included the three small provinces of Gévaudan, Velay,

and Vivarais (in its entirety), these three provinces being

to the northeast of Languedoc.

Some people also consider that the region around Albi

was a traditional province, called Albigeois (now département

of Tarn), although it is most often considered as being part

of Languedoc proper. The provinces of Quercy and Rouergue,

despite their old ties with Toulouse,

were not incorporated into the gouvernement of Languedoc,

instead being attached to the gouvernement of Guienne and

its far-away capital Bordeaux. This decision was probably

intentional, to avoid reviving the independently-spirited

county of Toulouse.

The Province of Languedoc covered an area of approximately

42,700 km² (16,490 sq. miles), roughly the region between

the Rhône

River (border with Provence) and the Garonne River (border

with Gascony), extending northwards to the Cévennes

and the Massif Central (border with Auvergne).

The governors of Languedoc resided in Pézenas,

on the Mediterranean

coast, away from Toulouse

but close to Montpellier.

In time they had increased their power well beyond military

matters, and had become the l administrators and executive

power of the province, a trend seen in the other gouvernements

of France, but particularly acute in Languedoc. In the Languedoc

the Duke of Montmorency, governor of Languedoc, openly rebelled

against the king, was defeated and beheaded in Toulouse

in 1632 by the order of Richelieu. The kings of France became

fearful of the power of the governors, so after King Louis

XIV (the Sun King) they had to reside in Versailles and were

forbidden to enter the territory of their gouvernement. Thus

the gouvernements became hollow structures, but they still

carried a sense of the old provinces, and so their names and

limits have remained popular until today.

For administrative purposes, Languedoc was divided in two

généralités, the généralité

of Toulouse

and the généralité of Montpellier,

the combined territory of the two generalities exactly matching

that of the gouvernement of Languedoc. At the head of a generality

was an intendant, but in the case of Languedoc there was only

one intendant responsible for both generalities, and he was

often referred to as the intendant of Languedoc, even though

technically speaking he was in fact the intendant of the generality

of Toulouse

and intendant of the generality of Montpellier.

The generality of Toulouse

is also referred to as Upper Languedoc (Haut-Languedoc), while

the generality of Montpellier,

down to the level of the sea, is referred to as Lower Languedoc

(Bas-Languedoc). The intendants of Languedoc resided in Montpellier,

and they had a sub-delegate in Toulouse.

Montpellier

was chosen specifically to diminish the power of Toulouse,

which symbolised the old spirit of independence of the county

of Toulouse,

and whose parlement was very influential. The intendants replaced

the governors as administrators of Languedoc, but appointed

and dismissed at will by the king, they were no threat to

the central state in Versailles. By 1789 they were the most

important element of the local administration of the kingdom.

The Parlement of Toulouse

For judicial and legislative matters, Languedoc was overseen

by the Parlement of Toulouse, founded in the middle of the

15th century. It was the first parlement created outside of

Paris by the kings of France in order to be the equivalent

of the Parlement of Paris in the faraway southern territories

of the kingdom. The jurisdiction of the Parlement of Toulouse

included the whole of the territory of the gouvernement of

Languedoc, but it also included the province of Rouergue,

most of the province of Quercy, and a part of Gascony. The

Parlement of Toulouse was the supreme court of justice for

this vast area of France, the court of last resort whose rulings

could not be appealed, not even to the Parlement of Paris.

The Parlement of Toulouse could also create case law through

its decisions, as well as interpret the law. It was also in

charge of registering new royal edicts and laws, and could

decide to block them if it found them to be in contravention

with the liberties and laws of Languedoc.

Taxation

For purposes of taxation, Languedoc was ruled by the States

of Languedoc, whose jurisdiction included only Languedoc proper

(and Albigeois), but not Gévaudan, Velay, and Vivarais,

which kept each their own provincial states until 1789. Languedoc

proper was one of the very few provinces of France which had

the privilege to decide over tax matters, the kings of France

having suppressed the provincial states in most other provinces

of the kingdom. This was a special favour from the kings to

ensure that an independently-spirited region faraway from

Versailles would remain faithful to the central state. The

States of Languedoc met in many different cities, and for

some time they established themselves in Pézenas,

but in the 18th century they were relocated definitively to

Montpellier,

where they met once a year, until 1789.

Ecclesiastical

For religious purposes, Languedoc was divided into a number

of ecclesiastical provinces.

Modern administrative divisions

Resulting from this intricate entanglement of administrations

and jurisdictions so typical of France before the French Revolution,

it is hard to say which city was the capital city of Languedoc.

Toulouse

and Montpellier

both often claim to be the capital of Languedoc. As a matter

of fact, in the 18th century the monarchy clearly favouredMontpellier,

a city much smaller than Toulouse,

and with less history and memories attached to it than the

ancient metropolis of Toulouse,

of which the kings of France were always fearful. However,

most people consider that Toulouse

is the real capital city of the province of Languedoc, due

to its old status as centre of the county of Toulouse,

and due to the mighty power of its parlement. On maps (both

ancient and modern) showing the provinces of France in 1789

(or rather the gouvernements), Toulouse

is always marked as the capital city of Languedoc.

The province of Languedoc has been divided between four modern-day

régions:

- 55.5% of its former territory lies in the Languedoc-Roussillon

région, capital city Montpellier,

covering the départements of Gard,

Hérault,

Aude,

Lozère,

and the extreme-north of Pyrénées-Orientales,

which account for 86.5% of the territory of Languedoc-Roussillon.

The remaining 13.5% is Roussillon

(Pyrénées-Orientales), a province which

was never part of Languedoc historically.

- 24.8% of its former territory lies in the Midi-Pyrénées

région, capital city Toulouse,

covering the département of Tarn, as well as the

eastern half of Haute-Garonne, the southeast of Tarn-et-Garonne,

and the Northwest and Northeast of Ariège, which

account for 23.4% of the territory of Midi-Pyrénées.

The remaining 76.6% is made of Quercy and Rouergue, as well

as the province of County of Foix (which had been a vassal

of the county of Toulouse

in the Middle Ages), several small provinces of the Pyrenees

mountains, and a large part of Gascony.

- 13% lies in the Rhône-Alpes région, covering

the département of Ardèche, which accounts

for 12.7% of the territory of Rhône-Alpes

- 6.7% lies in the Auvergne région, covering the

central and eastern part of the département of Haute-Loire,

which account for 11% of the territory of modern-day Auvergne

region

Population and cities

On the traditional territory of the province of Languedoc

there live approximately 3,650,000 people (as of 1999 census),

52% of these in the Languedoc-Roussillon région, 35%

in the Midi-Pyrénées région, 8% in the

Rhône-Alpes région, and 5% in the Auvergne région.

The territory of the former province shows a stark contrast

between some densely populated areas (coastal plains as well

as metropolitan area of Toulouse

in the interior) where density is between 150 inhabitants

per km²/390 inh. per sq. mile (coastal plains) and 300

inh. Per km²/780 inh. Per sq. mile (plain of Toulouse),

and the hilly and mountainous interior where density is extremely

low, the Cévennes area in the south of Lozère

having one of the lowest densities of Europe with only 7.4

inhabitants per km² (19 inh. Per sq. mile).

The five largest metropolitan areas on the territory of the

former province of Languedoc are (as of 1999 census): Toulouse

(964,797), Montpellier

(459,916), Nîmes

(221,455), Béziers

(124,967), and Alès (89,390).

The population of the former province of Languedoc is currently

the fastest-growing in France, and also among the fastest-growing

in Europe, as an increasing flow of people from northern France

and the north of Europe relocating to the sunbelt of Europe,

in which Languedoc is located. Growth is particularly strong

in the metropolitan areas of Toulouse

and Montpellier,

which are the two fastest growing metropolitan areas in Europe

at the moment. However, the interior of Languedoc is still

losing inhabitants, which increases the difference of density.

Population of the coast of Languedoc as well as the region

of Toulouse

is young, educated, and affluent, whereas in the interior

the population tends to be much older, with significantly

lower incomes, and with a lower percentage of high school

and especially college graduates.

Languedoc-Roussillon

Languedoc-Roussillon

(Occitan:

Lengadòc-Rosselhon; Catalan: Llenguadoc-Rosselló)

is one of the 26 regions of France. It comprises five departments,

and borders the other French regions of Provence-Alpes-Côte

d'Azur, Rhône-Alpes, Auvergne, Midi-Pyrénées

on the one side, and Spain, Andorra and the Mediterranean

Sea on the other side. Languedoc-Roussillon

(Occitan:

Lengadòc-Rosselhon; Catalan: Llenguadoc-Rosselló)

is one of the 26 regions of France. It comprises five departments,

and borders the other French regions of Provence-Alpes-Côte

d'Azur, Rhône-Alpes, Auvergne, Midi-Pyrénées

on the one side, and Spain, Andorra and the Mediterranean

Sea on the other side.

The region is made up of the following historical provinces:

68.7% of Languedoc-Roussillon was formerly part the province

of Languedoc: the departments of Aude,

Gard,

Hérault

the extreme south and extreme east of Lozère,

and the extreme north of Pyrénées-Orientales.

The former province of Languedoc also extends over the Midi-Pyrénées

region, including the old capital of Languedoc Toulouse.

17.9% of Languedoc-Roussillon was formerly the province of

Gévaudan: Lozère

department. A small part of the former Gévaudan lies

inside the current Auvergne region. Gévaudan is often

considered to be a sub-province inside the province of Languedoc,

in which case Languedoc would account for 86.6% of Languedoc-Roussillon.

13.4% of Languedoc-Roussillon, located in the southernmost

part of the region, is a collection of five historical Catalan

pays: Roussillon,

Vallespir, Conflent, Capcir, and Cerdagne, all of which are

in turn included -east to west- in the Pyrénées-Orientales

département. These pays were part of the Ancient Regime

province of Roussillon,

owning its name to the largest and most populous of the five

pays, Roussillon.

"Province of Roussillon and adjacent lands of Cerdagne"

was indeed the name that was officially used after the area

became French in 1659, based on the historical division of

the five pays between the county of Roussillon

(Roussillon and Vallespir) and the county of Cerdagne (Cerdagne,

Capcir, and Conflent).

Llívia is a town of Cerdanya, province of Girona,

Catalonia, Spain, that forms a Spanish exclave surrounded

by French territory (Pyrénées-Orientales

département).

Major

communities Major

communities

At the regional elections in March 2004, the socialist mayor

of Montpellier

Georges Frêche, a maverick in French politics, conquered

the region, defeating its center-right president. Since then,

Georges Frêche has embarked on a complete overhaul of

the region and its institutions. The flag of the region, which

displayed the cross of Languedoc as well as the Flag of Roussillon

(the "Senyera"), was changed for a new nondescript

flag with no reference to the old provinces, except in terms

of the colours (red and yellow), which are the colours of

both Languedoc and all the territories from the former Crown

of Aragon.

Frêche also wanted to change the name of the region,

wishing to erase its duality (Languedoc vs. Roussillon)

and strengthen its unity. Thus, he wanted to rename the region

"Septimanie" (Septimania), the name created by the

Romans at the end of the Roman Empire for the coastal area

corresponding quite well to present day Languedoc-Roussillon

(including Roussillon,

but not including Gévaudan), and used in the early

Middle Ages for the area. A strong opposition of the population

led to Georges Frêche giving up on his idea.

Catalan nationalists in Roussillon

would like the Pyrénées-Orientales

department to secede from Languedoc-Roussillon and become

a region in its own right, under the proposed name of "Catalunya

Nord" (Northern Catalonia).

On the other hand there are some who would like to merge

the Languedoc-Roussillon and Midi-Pyrénées regions,

reunifying the old province of Languedoc, and creating a large

region.

Prior to the 1960s, Occitan

and Catalan were the dominant languages of the area.

Occitan literature - still sometimes called Provençal

literature - is a body of texts written in Occitan

in what is nowadays the South of France. It originated in

the poetry of the eleventh- and twelfth- century Troubadours,

and inspired the rise of vernacular literature throughout

medieval Europe.

Music. Aimeric de Peguilhan, Giraut de Bornelh and

Bertran de Born were major influences in troubadour composition,

in the High Middle Ages. The troubadour tradition is associated

with originating from the region.

The Romantic music composer Déodat de Séverac

was born in the region, and, following his schooling in Paris,

he returned to the region to compose. He sought to incorporate

the music indigenous to the area in his compositions.

Wine. The Languedoc-Roussillon region is a major wine

producing area - the largest in the world - dominated by 740,300

acres (2,996 km2) of vineyards, three times the area of all

the vineyards in Bordeaux. The region has been an important

wine making centre for centuries. Grapevines are said to have

existed in the South of France since the Pliocene period -

before the existence of Homo sapiens. The first vineyards

of Gaul developed around two towns: Béziers

and Narbonne.

The Mediterranean

climate and plentiful land with soil ranging from rocky

sand to thick clay was very suitable for the production of

wine, and it is estimated that one in ten bottles of the world's

wine was produced in this region during the 20th century.

The region is the largest contributor to the European Union's

glut of wine known as the wine lake.

Sud de France. The Languedoc-Roussillon region has

adopted a marque to help market its products, in particular,

but not limited to, wine. The 'Sud de France' (Southern France)

marque was adopted in 2006 to help customers abroad not familiar

with the Appellation system to recognise those wines that

originated in the L-R area, but the marque is also used for

other products, some of which include cheeses, olive oils

and pies.

Provence

The present Languedoc

represents the southern half of the area covered by the

ancient Roman's first province outside Italy. The northern

part is now called Provence.

The area shares much common history with the Languedoc, having

successively been connected and disconnected over the centuries.

For more on Provence and its history, click on the following

link which will open a new window to Beyond

the French Riviera www.beyond.fr

Timeline

| 507: |

The Frankish king Clovis defeated the Visigoths in

the Battle of Vouillé. Afterwards, the child-king

Amalaric was carried for safety into the Iberian Peninsula.

Aquitania passed into the hands of the Franks, and Septimania,

with other Visigothic territories in Gaul, was ruled

by Amalaric's maternal grandfather, Theodoric the Great.

|

| 509: |

Theodoric the Great created the first kingdom of Septimania,

retaining its traditional capital at Narbonne.

He appointed as his regent an Ostrogothic nobleman named

Theudis.

|

| 522: |

The young Amalaric was proclaimed king.

|

| 526: |

Theodoric died. Amalaric assumed full royal power in

the Iberian Peninsula and Septimania, relinquishing

Provence to his cousin Athalaric. He married Clotilda,

daughter of Clovis, but found, as other royal husbands

of Merovingian princesses found, that the entanglement

brought on him the penalty of a Frankish invasion.

|

| 531: |

Amalaric lost his life in the Frankish invasion, and

Arian Visigothic Septimania was the last part of Gaul

to remain in Visigothic hands.

|

| 534: |

Prince Theudebert son of Theuderic of Austrasia (Merovingian

Frankish not Gothic) invaded Septimania in concert with

Prince Gunthar son of King Chlothar. Gunthar stopped

at Rodez and did not invade Septimania. Theudebert took

and held the country as far as Béziers

and Carbiriers from which he took the woman Deuteria

as a wife. Theudebert and his half brother Childebert

invaded Spain as far as Saragossa 534-538. At some point

soon after this, the Visigoths regained the territory

they had lost in Theudebert's invasion.

|

| 586: |

Merovingian King of Burgundy Guntram raised a force

to invade Septimania as a prelude to conquest of Spain.

His forces plundered from Nîmes

to Carcassonne

(where the Frankish Count Terentiolus of Limoges was

killed) but were unable to take the walled cities. Visigothic

Prince Recared came in response from Spain to Narbonne

and as far as Nîmes

and invaded nearby Frankish territories as far as Tolosa

for plunder and to punish the Franks for the invasion

(Gregory of Tours Book VIII 30-31 and 38). Frankish

rebel Dukes Desiderius and Austrovald at that time in

control of Tolosa raised an army and attacked Carcassonne.

Desiderius was defeated and killed and Austrovald retreated

with his for Tolosa (Gregory of Tours Book VIII 44).

|

| 587: |

Septimania came under Catholic Rule in 587 with the

conversion of Recared, who had become the King of the

Visigoths in 586 with his father, Leovigild's death.

At that time Arian Bishop Athaloc and Counts Granista

and Wildigern revolted against Recared in Septimania

but were defeated (Gregory of Tours Book IX 15 and John

of Biclar) Most of the Christian population of the province

were already Catholic and Arian Christians largely converted

with the death of Athaloc soon after Recared's conversion.

|

| 589: |

Merovingian King of Burgundy Guntram again tried to

invade Septimania sending Austrovald to Carcassonne

and Boso and Antestius to other cities. King Recared

sent General Claudius who defeated the Franks and preserved

the territory of Septimania under Visigothic Rule.

|

| 719: |

The Moors over-ran Septimania.

|

| 720: |

Al-Samh set up his capital at Narbonne,

which the Moors called Arb?na. He offered the still

largely Arian inhabitants generous terms.

Al-Samh quickly pacified the other cities. With Narbonne

secure, and equally important, its port, for the Arab

mariners were masters now of the Western Mediterranean

, he swiftly subdued the largely unresisting cities,

still controlled by their Visigoth counts: taking Alet

and Béziers,

Agde, Lodève, Maguelonne and Nîmes

|

| 721: |

By now Al-Samh was reinforced and ready to lay siege

to Toulouse,

a possession that would open up Aquitaine to him on

the same terms as Septimania. But his plans were overthrown

in the disastrous Battle of Toulouse (721), with immense

losses, in which al-Samh was so seriously wounded that

he soon died at Narbonne.

|

| 720's: |

Arab forces soundly based in Narbonne

and easily resupplied by sea, struck eastwards.

|

| 725: |

Arab raid on Autun.

|

| 731: |

The Berber wali of Narbonne

and the region of Cerdanya, Uthman ibn Naissa, called

"Munuza" by the Franks, who was recently linked

by marriage to duke Eudes of Aquitaine, revolted against

Córdoba, and was defeated and killed.

|

| 732: |

October: An Islamic invasion force made up primarily

of Berber and Arab cavalry under Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi

encountered Charles Martel and his veteran Frankish

army between Tours and Poitiers and was defeated, and

Abd er-Rahman was killed, at what the majority of historians

consider the macrohistorical "Battle of Tours"

that stopped the Moorish advance.

|

| |

|

| |

Frankish Conquest |

| 732: |

The Franks took the territory round Toulouse.

Charles Martel directed his attention to Narbonne.

|

| 737: |

Charles Martel destroyed Arles, Avignon, and Nîmes,

but unsuccessfully attacked Narbonne,

which was defended by its Goths, and Jews

under the command of its governor Yusuf, 'Abd er-Rahman's

heir. Having crushed the relief force at the River Berre,

he left Narbonne

isolated.

around 747: The government of the Septimania region

(and the Upper Mark, from the Pyrenees

to the river Ebro) was given to Aumar Ben Aumar.

|

| 752: |

The Gothic counts of Nîmes,

Melguelh, Agde and Béziers

refused allegiance to the emir at Córdoba and declared

their loyalty to the Frankish king. The count of Nîmes,

Ansemund, had some authority over the remaining counts.

The Gothic counts and the Franks then began to besiege

Narbonne,

where Miló was probably the count (as successor

of the count Gilbert), but Narbonne

resisted. |

| 754: |

An anti-Frank reaction, led by Ermeniard, killed Ansemund,

but the uprising was without success and Radulf was

designated new count by the Frankish court.

About 755: Abd al-Rahman Ben Uqba replaced Aumar Ben

Aumar.

|

| 759: |

Charles Martel's son, Pippin the Younger besiegedNarbonne,

which capitulated. The county was granted to Miló,

who was the Gothic count in Muslim times. |

| 760: |

The Franks took the region of Roussillon. |

| 767: |

After the fight against Waifred of Aquitaine, Albi,

Rouergue, Gévaudan, and the city of Toulouse

were conquered. |

| 777: |

The wali of Barcelona, Sulayman al-Arabi, and the wali

of Huesca, Abu Taur, offered their submission to Charlemagne

and also the submission of Husayn, wali of Zaragoza. |

| 778: |

Charlemagne invaded the Upper Mark. Husayn refused allegiance

and Charlemagne had to retreat. |

| 778: |

August 15: In the Pyrenees

, the Basques defeated Charlemagne's forces in the Roncesvalles.

Charlemagne found Septimania and the borderlands so devastated

and depopulated by warfare, with the inhabitants hiding

among the mountains, that he made grants of land that

were some of the earliest identifiable fiefs to Visigothic

and other refugees. He also founded several monasteries

in Septimania, around which the people gathered for protection.

Beyond Septimania to the south Charlemagne established

the Hispanic Marches in the borderlands of his empire.

Septimania passed to Louis, king in Aquitaine, but it

was governed by Frankish margraves and then dukes (from

817) of Septimania. |

| 826: |

The Frankish noble Bernat of Septimania (also, Bernat

of Gothia) became ruler of Septimania and the Hispanic

Marches and ruled them until 832. His career characterised

the turbulent 9th century in Septimania. His appointment

as Count of Barcelona in 826 occasioned a general uprising

of the Catalan lords at this intrusion of Frankish power.

For suppressing Berenguer of Toulouse

and the Catalans, Louis the Pious rewarded Bernat with

a series of counties, which roughly delimit 9th century

Septimania: Narbonne,

Béziers,

Agde, Magalona, Nîmes

and Uzès. |

| 843: |

Bernard rose against Charles the Bald. |

| 844: |

Bernard was apprehended at Toulouse

and beheaded. |

| |

|

|