Where was the The Shroud before it came into public view at Lirey

during its ownership by Geoffrey de Charnay. Was it hidden in the

Languedoc?

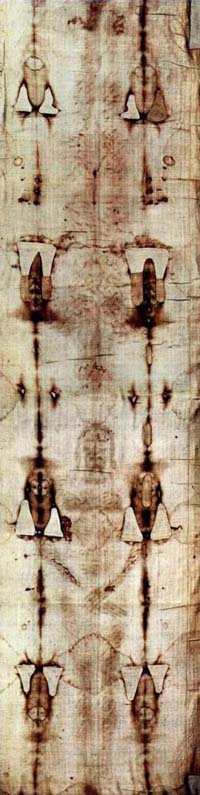

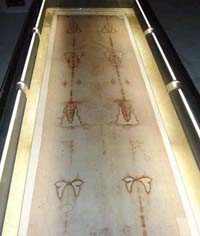

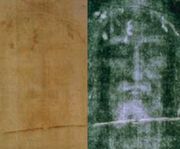

The

Shroud of Turin (or Turin Shroud) is a linen cloth bearing the hidden

image of a man who appears to have been physically traumatized in

a manner consistent with crucifixion. It is kept in the royal chapel

of the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, Italy. Despite

extensive evidence that it is a medieval fraud it is still believed

by many Roman Catholics to be a cloth worn by Jesus Christ at the

time of his burial. The

Shroud of Turin (or Turin Shroud) is a linen cloth bearing the hidden

image of a man who appears to have been physically traumatized in

a manner consistent with crucifixion. It is kept in the royal chapel

of the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, Italy. Despite

extensive evidence that it is a medieval fraud it is still believed

by many Roman Catholics to be a cloth worn by Jesus Christ at the

time of his burial.

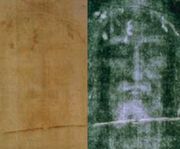

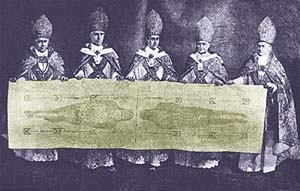

The image on the shroud is clearer and more striking in black-and-white

negative than in its natural sepia color. The negative image was

first observed on May 28, 1898 on the reverse photographic plate

of an amateur photographer, Secondo Pia, who was allowed to photograph

it as part of an exhibition for Turin Cathedral.

The origin of the shroud is disputed. Researchers have coined the

term sindonology to describe its general study (from Greek sindon,

the word used in the Mark Gospel to describe the cloth that Joseph

of Arimathea bought to use as Jesus' burial cloth).

According to some, the Shroud's history can be traced back to biblical

times, a couple of missing centuries being accounted for by the

shroud being hidden by cathars in the Languedoc. The case is put

most cogently Jack Markwardt. Below is a copy

of his paper putting the case for this theory , with annotations

by the webmaster.

Description

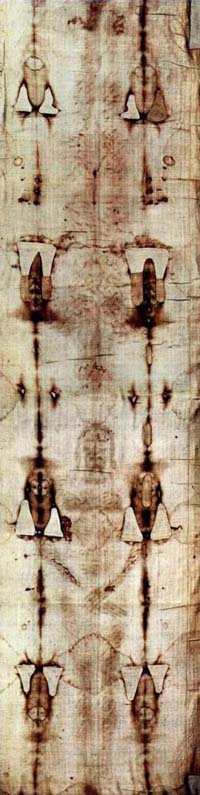

The

cloth is rectangular, measuring about 4.4 × 1.1 m (14.3 ×

3.7 ft). The cloth is woven in a three-to-one herringbone twill

composed of flax fibrils. It displays a faint, yellowish image of

a front and back view of a naked man with his hands folded across

his groin. The two views are aligned along the midplane of the body

and point in opposite directions. The front and back views of the

head nearly meet at the middle of the cloth. These views are consistent

with an orthographic projection of a human body. The

cloth is rectangular, measuring about 4.4 × 1.1 m (14.3 ×

3.7 ft). The cloth is woven in a three-to-one herringbone twill

composed of flax fibrils. It displays a faint, yellowish image of

a front and back view of a naked man with his hands folded across

his groin. The two views are aligned along the midplane of the body

and point in opposite directions. The front and back views of the

head nearly meet at the middle of the cloth. These views are consistent

with an orthographic projection of a human body.

The "Man of the Shroud" has a beard, moustache, and shoulder-length

hair parted in the middle. He is muscular. Various experts have

measured him as from 1.75 m, or roughly 5 ft 9 in, to 1.88 m, or

6 ft 2 in). Reddish brown stains are found on the cloth, showing

various wounds that correlate with the yellowish image, the pathophysiology

of crucifixion, and the Biblical description of the death of Jesus.

- one wrist bears a large, round wound, apparently from piercing

(the second wrist is hidden by the folding of the hands)

- an upward gouge in the side penetrating into the thoracic cavity

- small punctures around the forehead and scalp

- scores of linear wounds on the torso and legs claimed to be

consistent with the distinctive wounds of a Roman flagrum.

- streams of blood down both arms that include blood dripping

from the main flow in response to gravity at an angle that would

occur during crucifixion

- no evidence of either leg being fractured

- large puncture wounds in the feet as if pierced by a single

spike

more on:

History

of the Shroud

Theories

of how the image on the shroud was formed

Scientific

analysis of the Shroud

Analysis

of the Image as a Work of Art

Reasons

to Doubt the Shroud's Authenticity

Jack

Markwardt's paper putting the case that the shroud was hidden in

the Languedoc

Was The Shroud In Languedoc During The Missing

Years?

Copyright Jack Markwardt, 1997 (webmaster's notes

on the right)

|

INTRODUCTION: In 1204, a sydoine, bearing

a full-length figure of Christ and a possible Apostolic pedigree,1 disappeared from Constantinople. Matching that cloth

with the Shroud which appeared in Lirey, France a century

and a half later requires an accounting of its hidden movements

and an explanation for its acquisition by Geoffrey de Charny.

This paper focuses upon the "Missing Years" in the history

of the Shroud of Turin,2 presents

a hypothetical reconstruction of several of the more mysterious

chapters in the cloth's biography, and suggests that the sindonic

path between Constantinople and Lirey runs directly through

Languedoc.

|

The is an assumption here that the

sydoine that disappeared from Constantinople is the same artifact

we now know as the shroud of Turin. This has never been established

for certain.

|

|

1204: FROM CONSTANTINOPLE TO LANGUEDOC.

In April of 1204, the Fourth Crusade attacked Byzantine Constantinople

and, in the resultant chaos, someone pilfered the Emperor's

cloth. If the thief had held orthodox beliefs or had viewed

the Shroud as a sacred relic, he would not have kept it concealed

for long, but, instead, would have promptly claimed the credit

and wealth attendant to its ownership.3

Thus, the perpetrator probably had no affiliation to either

the Crusade or the Church of Rome and probably considered

the cloth to be something other than a purely religious artifact.

In this regard, it is critical to note that, at the precise

time of its disappearance, the Shroud was being treated less

as a holy relic than as a palladium wielded by the Emperor,

in weekly public exhibitions, against the military threat

posed by the crusaders.4 In fact, for the preceding six and a half centuries,

the Shroud, assuming its affinity to the Mandylion,5 had enjoyed a fabled reputation as a cloth possessing

great powers of protection. In 544, it had reportedly saved

the city of Edessa from a siege by the Persian army.6

|

The identification of the sydoine with

the Mandylion has not been established for certain.

|

|

Thereafter, the cloth not only maintained its

status as Edessa's holy palladium,7

but it also served as the model for numerous copies which

were similarly employed as palladia throughout the Eastern

empire.8 The protective virtues

of such images were described by Edward Gibbon as follows:

"In the hour of danger or tumult their venerable presence

could revive the hope, rekindle the courage, or repress the

fury of the Roman legions".9 In

the sixth century, Pope Gregory commissioned his own copy

of the image and had it brought to Rome where it was subsequently

invoked for protection by Popes of the eighth and ninth centuries.10

In 944, the Byzantine Emperor forcibly compelled the transfer

of the original image from Edessa to Constantinople in order

to obtain "a new, powerful source of divine protection" for

the capital city.11 Consequently,

the peoples of Edessa and Constantinople came to view relics

as possessing "palladian virtues which could protect them

from their enemies".12

|

Substantially accurate

|

|

In 1204, when the Shroud disappeared, two sects

of religious dualists, the Bogomils and the Paulicians, were

openly practicing their faith in Constantinople and, as will

be shown, possessed both the opportunity and the motive to

take and conceal the cloth. During the preceding century,

Eastern dualism had made its way to Western Europe13 and, by 1160, permeated Languedoc14 in the form of Catharism.15

Condemned by the Council of Tours in 1163,16

the heresy

continued to spread despite ever- increasing persecution

by the Church.17 All the while,

the Cathars

remained part of a single dualist communion with their brethren

in the East18 and maintained such extremely close ties with them19

that they themselves were frequently referred to as Bogomile

or Paulician.20 In 1172, Nicetas,

the dualist bishop of Constantinople, travelled to Languedoc

as a representative of the Eastern mother church,21

and, presiding over a Synod,22

persuaded the Cathars

to adopt an absolute form of dualism,23

reconsecrated Cathar bishops, and approved reformation of

the Cathar hierarchy.24 The dualists of the East provided Cathars

with scriptures25 and answers to

their religious questions26 and

some moved West and became involved in the political and religious

affairs of Languedoc.27 This federation of Eastern and Western dualists was

maintained for many decades and, in 1224, the Easterners were

to offer their homes to Cathar refugees and send them a spiritual

leader.28

|

The links between the various Dualist

groups is well established - but an important point, not mentioned

here, is that none of these Dualist groups accepted Christ's

bodily crucifixion, much less the survival of his burial cloth.

Furthermore, they detested all supposed religious relics without

exception.

|

|

In 1198, Innocent III became Pope and promptly

demonstrated a proclivity to use military force whenever convenient

to accomplish his religious and political goals29

and his fanatical hatred of heresy

drove him to seek the elimination of Catharism in Languedoc.30

Thus, in 1204, and at the precise time when the Cathars

desperately required protection from Innocent, their religious

brethren in the East31 were, week

after week, witnessing the exhibition and representation of

the Shroud as a tried, true and mighty palladium. As Ian Wilson

observed, the opportunity to take the cloth presented itself

to some Byzantine who had access to it during the confusion

of the crusader attack upon the city.32

Greek dualists enjoyed friendly contacts with the upper classes

of the capital33 and harbored little

love for a Church which had not only sent a Crusade to lay

siege to their city, but had resolved to exterminate their

fellow religionists in Languedoc. This paper suggests that

it was they who snatched the relic, concealed it, and sent

it to their persecuted brethren in Languedoc, not as an object

of religious veneration,34 but

as a powerful palladium which could be employed against the

fanatically-militant Church of Rome.

|

All accurate except that there is no

evidence that the shroud was taken to the Languedoc or that

the Cathars

ever used a palladium - which their religion regarded as worthless.

|

|

If these Greek dualists did send the Shroud

to Languedoc,35 they would have

entrusted it only to someone who could provide for its safekeeping

and ultimate deployment in the hour of need. Fortunately for

the Cathars,

they had a wealthy, powerful, and pugnacious champion who

could do so. Esclarmonde de Foix, the widowed sister of the

count of Foix, was a vociferous opponent of the Church36 and the patroness of a great complex of heretical workshops,

schools, and hostels in Pamiers.37

In 1204, the year of the Shroud's disappearance, she was ordained

a Perfect,38 the highest order of the Cathar hierarchy, and sponsored

the fortification of Montsegur,39

a castle stronghold which had collapsed into ruins.40

If the coincidental kidnapping of the Shroud and the fortification

of Montsegur were, in fact, part and parcel of the same Cathar

defense program, the cloth would likely have been sent to

Esclarmonde, in Pamiers, with the expectation that, when needed,

she would take it to Montsegur where its fabled powers of

protection could be invoked to save Cathars,

just as they had once been unleashed to rescue Edessa from

the Persian army.41

|

Speculative. Esclaremonde did indeed

receive the consolamentum and so become a Perfect, but this

was not the "highest order of the Cathar hierarchy".

The most senior Cathars

in the area were Cathar Bishops, who did not count Esclaremond

among their number. Also, it is not clear who ordered Montsegur

to be refortified, though it certainly was refortified to

provide defense against the coming Catholic Crusader army.

|

|

1204-1244: THE PALLADIUM OF HERETICS.

There is circumstantial and anecdotal evidence that, from

1204 to 1244, the Shroud was kept as a palladium by the Cathars

of Languedoc:

|

|

|

(1) 1205-1207: The Appearance of the Grail

in Languedoc. The Holy

Grail has been connected to the Shroud,42 the Cathars,43

and Esclarmonde.44 Between approximately

1205 and 1207,45 Wolfram von Eschenbach46 wrote a Grail

legend, Parzival, which contained several apparent

allusions to the Shroud47 and placed

the Grail in Munsalvaesche, a name denoting a mountainous

region of safety, very much like Languedoc, in general, and

Montsegur,

in particular.48 Wolfram's Grail

was guarded by

Templars who wore white surcoats with red crosses49

and, at that precise time, the Temple Order in Languedoc had

been thoroughly infiltrated by persons from Cathar families

or holding Cathar sympathies.50 In another poem, Wolfram named the lord of the Grail

castle as Perilla,51 a transparent

nameplay on Raymond de Perella, the lord of Montsegur from

at least 1204 to 1244. Finally, in an unfinished work, Wolfram

situated the Grail castle in the Pyrenees52 which border on Languedoc and lie quite near to Montsegur.53

|

There are fascinating hints that Wolfram

von Eschenbach made reference to Montsegur,

but that is not relevant to this argument.

Also it is questionable whether the

Cathars

were in any way associated with the Templars

- certainly no evidence is offered here.

|

|

(2) 1207: The Pope's Call for a Languedoc

Crusade. In 1203, the so-called cult of relics influenced

the diversion of the Fourth Crusade to Constantinople for

purposes of rescuing relics from the schismatic Greeks.54

By 1207, as Parzival clearly demonstrates, some had

concluded that the Shroud was held captive by the heretics

of Languedoc. On November 12, 1207, Innocent called for a

crusade against the Cathars;55

however, a palpable pretext for crusade did not materialize

until two months later when a papal legate was murdered by

a servant of Raymond VI, the Count

of Toulouse.56 Raymond's pleas for absolution were rejected by the

Church in what Jonathan Sumption called "a scandalous breach

of ecclesiastical law accomplished solely to excuse a military

invasion of Raymond's dominions".57

Despite the Cathars

having nothing to do with the murder, the Pope urged military

action against them.58 By 1209, Raymond had completely capitulated to the Church

and the Pope's plan to punish him was officially abandoned.59 Nevertheless, Innocent pushed forward with his war against

the heretics, thus establishing that this crusade had always

been designed to attack the Cathars,

possibly to liberate the Shroud in furtherance of the goals

of the cult of relics.

|

Innocent III's character is fairly

represented here - but his objectives appear to have been

to stop the whole region deserting the Catholic

Church in favour of the Cathar Church. He certainly had

other motives (his new claims to temporal power, the recovery

of property claimed by the Church and the reintroduction of

clerical taxation for example), but there is no evidence for

this assertion, especially as the Crusades against the Cathars

continued for a generation before Montsegur was attacked.

Also it is significant that the attack in 1244 was the direct

result of a series of incidents in 1242 - long after Innocent's

death in 1216.

|

|

(3) 1209-1229: The Cathars' Three-Nail Crucifixion.

In the early thirteenth century, the Crucifixion was typically

depicted with Christ affixed to the cross with four nails,

one placed through each of his hands and feet.60

During the Albigensian Crusade, reports were circulated of

a three-nail crucifixion, prompting Innocent to proclaim an

official four-nail dogma and resulting in the condemnation,

as heretics, of anyone who asserted the use of three nails.61 In an attempt to win converts, some Cathars

employed a crucifix which had no upper arm, the feet of Christ

crossed, and three nails.62 There

is no apparent explanation of why Cathars,

who rejected the reality of Christ's death,63 would assert a three-nail crucifixion or employ a three-nail

crucifix, particularly when attempting to proselytize orthodox

believers who were accustomed to, and who were bound to believe

in, a four-nail portrayal. A close examination of the Shroud

reveals that only one nail pierced Christ's feet64

and the Cathars'

possession of the cloth with its evidence of the use of one

nail through both feet would explain their assertion of a

three-nail crucifixion which contradicted the traditional

and papally-mandated beliefs of the orthodox.

|

As noted here Cathars

rejected the reality of Christ's crucifixion. The assertion

that some Cathars

employed a crucifix which had no upper arm, the feet of Christ

crossed, and three nails is not reliably referenced and is

at odds with Cathar theology. (This does not mean that other

so-called heretics could not have preserved this ancient tradition

about the crucifixion - modern science has only recently revealed

the many varieties of crucifixion employed by the Romans)

|

|

(4) 1218-1224: The Cathars and the Flesh

and Blood of Christ. Joinville's History of St. Louis

contains an anecdotal story which, for many centuries,

has been employed to strengthen faith in the sacrament of

the Eucharist. According to this account, Amaury de Montfort,

while leading the Albigensian Crusade,65

declined a Cathar invitation to come and see the body of Christ

"which had become flesh and blood in the hands of the priest".66

The Cathars

rejected Christ's incarnation and believed that his humanity

was merely symbolic.67 For Cathars,

there never was a body of Christ which could have become flesh

and blood in the hands of their priest. In addition, the Cathars

rejected the sacraments, including the Eucharist, as being

vain and useless68 and their priests

did not say Mass or make sacrifices of the altar.69 Instead, Cathars

performed a simple daily benediction of bread and wine while

reciting the Lord's Prayer.70 For Cathars,

there was no ceremony or rite by which the body of Christ

could have become flesh and blood in the hands of their priest.71

Cathars

considered lying to be abhorrent72

and their Perfects, who were forbidden to engage in any trade

which would expose them to lying or fraud,73 refused to prevaricate, even to save their own lives.74

Since Cathars

would not have fabricated any claim, especially one which

would repudiate their own religious beliefs, it appears that

they invited Amaury to view a cloth which, when displayed

in the hands of their priest, manifested a mysterious image

of the flesh and blood of Christ. The Amaury story was written

prior to 1272,75 a mere fifty years after the event which it describes,

and was related, no doubt, to inspire readers to emulate a

pious virtue admired by St. Louis;76

however, it appears to have a factual and historical basis,

particularly in light of other circumstantial evidence which

demonstrates that, during the precise period of the story's

setting, the Cathars

were in possession of the Shroud.

|

The story needs to be stretched beyond

breaking point to accommodate this theory. Moreover medieval

hagiographies are exceptionally unreliable and the idea that

Cathars

would entertain the idea of the body of Christ becoming "flesh

and blood in the hands of the priest" is not tenable

- it could only be the invention of a Catholic mind unfamiliar

with Cathar theology. The obvious explanation is that the

story was fabricated, not that it was a true story referring

obliquely to a piece of cloth.

|

|

(5) 1209-1244: The Mystical Cathar Treasure

of Montsegur. After the outbreak of the Albigensian Crusade

in 1209, Esclarmonde took up residence in Montsegur

and, in 1215, presided there over a Cathar court.77

Likewise, in 1209, the most important Cathar prelate, Guilhabert

de Castres,78 moved to Montsegur79

and, for the next thirty years, used it as his base for missionary

activities80 and the site of a Cathar Synod in 1232.81 In approximately 1240, Guilhabert was succeeded by Bertrand

de Marty82 who remained at Montsegur

until its fall in 1244.83 As previously

mentioned, from at least 1204 to 1244, Raymond de Perella,84

a vassal to Esclarmonde's brother and a man with strong sympathies

for the heretics, served as the lord of Montsegur.85

If the Shroud was taken to Montsegur, knowledge of its presence

there was likely limited to a privileged few who undoubtedly

ascribed the castle's survival through more than three decades

of crusade and persecution to the linen palladium.86

So long as the Cathar hierarchy was headquartered in Montsegur,

it is inconceivable that the Shroud would have been taken

elsewhere. Coincidently, throughout the Crusade, Montsegur

was rumored to hold a mystical Cathar treasure which far exceeded

material wealth.87 In January of

1244, with Montsegur

under siege, all of the gold, silver and money which had been

stored there was taken out and hidden in the forests of the

Sabarthes mountains.88 In February, the Montsegur garrison left the castle

and launched an attack which ended in disaster and compelled

surrender on March 2.89 The Cathars

sought and obtained a fifteen-day truce90

which permitted them to hold a festival91and,

when the truce expired on March 16, more than two hundred

Perfects were thrown into a burning pyre.92 That same night, four Cathars,

who had been concealed,93 used

ropes to scale down Montsegur's

steep western rock-face,94 and,

according to tradition, they took with them the mystical Cathar

treasure.95 This paper suggests that the mystical treasure was,

or included, the Shroud and that the Cathars

had procured the truce in a desperate, but unsuccessful, attempt

to invoke their palladium's legendary powers96

during the closing weeks of the season of its origin--Easter.97

|

Difficult to square with the fact that

for most of the 10 month siege the defenders were able to

communicate easily with the outside world, so would have been

able to get any material items out of the castle and away

to a more remote site such as Usson.

There is no reason to suppose that

the treasure was a piece of cloth - most commentators believe

it to have been ancient Gnostic texts if it was anything material.

Another unlikely theory is that it

was the Holy

Grail. Another is that it was the treasure later discovered

by Abbé

Bérenger Saunier at Rennes-le-Château.

|

|

1244-1349: THE PROPERTY OF HERETICS AND

THEIR DESCENDANTS. The four escapees from vanquished Montsegur

carried the treasure to a valley in the Sabarthes,98

a region loyal to the Cathar cause and home to the heretical

Auteri family.99 Approximately fifty years later, an Auteri descendant,

Peter, assumed leadership of a Cathar organization which was

still active100 but persecuted relentlessly by the Inquisition.101 After Peter Auteri was captured and executed in 1311,102

the heretical community began to disintegrate.103

In 1320, a group of Cathars

were forced to recant in Albi104

and, the following year, the last Cathar Perfect, William

Belibasta, was lured from hiding in Catalonia and burned to

death.105 Between 1318 and 1326,

Jacques Fournier, the future Pope Benedict XII, prosecuted

the Carcassonne

Inquisition from Pamiers and walled up a Cathar remnant in

the caves of Lombrives, located in the Sabarthes.106

Thereafter, scattered groups of heretics and isolated individuals

carried on occasional guerrilla warfare,107

but, by 1350, the two-century struggle between the Church

and the Cathars

of Languedoc was brought to a close.108

|

These statements are correct, but it

is not clear what they seek to establish.

|

|

This paper suggests that, from 1244 to approximately

1349, the Shroud was kept in Languedoc, most probably in the

Sabarthes, by heretical families descended from the survivors

of Montsegur.109 Title to the relic could not legally pass from one

generation to another inasmuch as heretics, their sympathizers,

and their descendants were prohibited from making a will or

receiving a legacy.110 In addition, all personal property of heretics, their

sympathizers, and their descendants was required to be confiscated

and forfeited to the crown.111

Consequently, for a little more than a century, the Shroud

was scrupulously kept concealed in a region where survival

itself depended on secrecy112 and,

upon the deaths of its respective heretical owners, the cloth

was quietly handed down to surviving family members.

|

Possible, but no more than speculation.

|

|

In October of 1347, the Black Death swept into

Europe, ultimately killing more than a third of its population.113 Some towns with a population of 20,000 were left with

a mere 200 and, in certain of the smaller villages, only 100

out of 1,500 survived.114 The Plague

struck Marseille in January of 1348, with mortality rates

of up to 60% and, by summer, had reached Montpellier, Carcassonne,

and Toulouse.115 Montpellier's

ultimate loss of life was so extensive that Italian merchants

were granted citizenship rights just to allow the city to

be repopulated.116 In Perpignan, just north of the Spanish border and

not too distant from the region of heretical safe havens,

the Plague killed 90% of the municipal physicians and barber-surgeons

and 65% of the notaries.117 In

Avignon, up to two-thirds of the population died,118and

between February and May of 1349, as many as 400 of its people

were killed every day.119 The Pope's physician, who advised Clement VI to flee

the city until the Plague subsided,120

ultimately estimated that three-quarters of the entire population

of France had been killed.121 In

rural Languedoc, already devastated by famine and war, the

Black Death killed close to 50% of the population.122 In 1350, the Plague killed King Alphonso XI of Spain,123

but finally ran its course in the Mediterranean Basin.124

By that time, however, it is statistically probable that,

somewhere in the hill country of rural Languedoc, the heretical

family that possessed the Shroud had been killed and that

the cloth, as part of that family's possessions and personal

effects, had been, or would soon be, confiscated and forfeited

to the crown.

|

There seems to be an assumption of

high mortality rates everywhere - not the case in remote areas

like the Sabarthes, that a whole extended family died of the

plague (unlikely but possible), and also that there were no

trusted Cathar neighbours to take over stewardship.

Also, by this time there were no known

heretic families. The Inquisition had exterminated all the

known families, so any surviving Cathars

were not known as Cathars

and so were not liable to have their goods forfeited.

On top of this, much of the area still

belonged to the King of Aragon at this time, so confiscations

would go to him, not the King of France.

Cathars

still thrived in northern Italy and probably Catalonia so

they would have been more obvious places to keep a precious

object.

|

|

1349-1354: THE ACQUISITION OF THE SHROUD

BY GEOFFREY DE CHARNY. Wilson astutely observed that the

question of how the Shroud came to be owned by Geoffrey de

Charny lies at the very core of the Missing Years mystery.125

Historical evidence indicates that Geoffrey acquired the relic

between April of 1349 and January of 1354.126 Yet, there is no record of a military campaign,127 a gift,128 or an inheritance

which would have brought the Shroud to Geoffrey after 1349

and, in fact, throughout 1350 and during the first six months

of 1351, Geoffrey was held as a prisoner of war in England.129

|

|

|

Although it may have been unusual for Geoffrey

to have come to own the Shroud,130

the virtually unquestionable personal integrity131

of "the wisest and bravest knight of them all"132

would never have allowed him to obtain the cloth under dishonorable

circumstances or by the employment of improper means. Thus,

the mystery's solution must lie along a rightful and legal

path, and one such channel was opened to Geoffrey in the Spring

of 1349. At that time, Geoffrey held a life annuity of 1,000

livres, payable directly from the royal treasury. On April

19, 1349, this annuity was modified to 500 livres payable

to Geoffrey and his heirs from the first forfeitures which

might occur in the Languedoc senechaussees of Toulouse, Beaucaire,

and Carcassonne.133

|

|

|

This paper suggests that, subsequent to April

19, 1349, the Shroud was discovered among the confiscated

and forfeited personal goods of a Languedoc heretical family,

perhaps one victimized by the Black Death, and that Geoffrey

de Charny, by right of royal grant, legally and rightfully

acquired title to the relic. Given the location of the Sabarthes

and the other likely areas of heretical safe havens, the Shroud

forfeiture probably occurred in the seneschalsy of Carcassonne

where Geoffrey's trusted bailiff would have confiscated the

forfeited property even if Geoffrey himself was being held

in captivity.134 In Languedoc,

local bailiffs administered both high and low justice, arrested

heretics, pursued lawbreakers through the mountains, and attempted

to recover stolen objects.135 A forfeiture precipitated by the Plague would have

probably taken place in 1349 or 1350 and Geoffrey could have

been aware of his acquisition of the Shroud either before

he was taken prisoner at Calais on December 31, 1349 or during

his imprisonment in London through June of 1351.136

Such knowledge may have been responsible for the melancholy

religious poetry which Geoffrey authored during the period

of his captivity.137

|

|

|

1349-1390: PERPETUAL SILENCE AND THE MISSING

YEARS. Geoffrey has never been quoted as relating the

manner in which he acquired the Shroud and Wilson speculated

that something in the cloth's biography may have caused his

silence.138 If this is the explanation,

it may have been either a Cathar or a Templar

history; however, there is another possibility.

|

|

|

Given Geoffrey's noble character and personal

integrity, it is virtually certain that he fully reported

the circumstances of his acquisition to the Pope in Avignon.139

Indeed, a report and petition, together with papal approval,

was surely a prerequisite to holding the Lirey Shroud exhibitions

of the 1350's,140 and the Pope would never have permitted the relic to

become the object of worldwide pilgrimage141

unless he knew exactly how Geoffrey had acquired it and was

convinced that it was genuine; i.e., the Shroud was the same

cloth as that which had disappeared from Constantinople. Once

the Pope had learned of the reasons underlying the Languedoc

forfeiture, he would have deduced that Cathars

and their descendants had been the Shroud's keepers for a

century and a half and concluded that a disclosure of such

information might embarrass the Church, raise questions concerning

the motives for the Albigensian Crusade, create empathy for

Cathars

who had preserved Christianity's most precious relic, prejudice

the Church's ongoing prosecution of heresy

, and/or expose the relic to attack as the forgery or

idol of heretics. In addition, had it become known that the

cloth was only recently discovered among the personal effects

of Plague victims, it may have aroused fear of contamination

and a clamor for the destruction of the relic. Finally, a

disclosure of the Shroud's genesis may have precipitated a

demand from the Byzantine Emperor or the Eastern Orthodox

Church that the relic be returned to Constantinople.

|

Geoffrey's noble character does not

preclude him from being the victim of a hoax.

|

|

This paper suggests that, for these and/or

other reasons, the Pope ordered Geoffrey and his family to

remain perpetually silent on the subject of how the cloth

had been acquired and, on that specific condition, authorized

the exhibitions of the Shroud which were held in Lirey during

the 1350's. Geoffrey, ever the perfect knight and obedient

servant of king and Church, would have dutifully complied

with the Pope's directive and would have never publicly spoken

of how he had come into possession of the relic, thereby keeping

the information secure among himself, his wife, and their

son, Geoffrey II.142

|

|

|

In approximately 1389, Geoffrey's son initiated

a new round of Shroud exhibitions and Pierre D'Arcis, the

Bishop of Troyes, attempted to terminate them. In a draft

memorandum, which probably never reached Pope Clement VII

in Avignon,143 D'Arcis claimed

that the cloth was a cunningly-painted fraud, offered to supply

the Pope with all relevant information "from public report

and otherwise", and expressed a desire to speak personally

to the Pope due to his inability, in writing, to sufficiently

express "the grievous nature of the scandal, the contempt

brought upon the Church and ecclesiastic jurisdiction, and

the danger to souls".144 D'Arcis' reference to ecclesiastic jurisdiction appears

directly related to the Inquisition's ongoing prosecution

of heretics145 and his allusion

to scandal indicates that he had learned something of the

relic's heretical, but not of its Byzantine, history. In any

event, Clement was already familiar with the Shroud's Cathar

biography and Constantinople pedigree through the records

of his predecessors and/or his familial relationship with

Geoffrey's son.146 There is no evidence of the Pope's having requested

any elaboration from D'Arcis or having conducted any investigation

whatsoever. Instead, Clement permitted the Shroud exhibitions

to continue (subject to rather trivial conditions) and he

twice sentenced D'Arcis to the same perpetual silence as that

which had previously bound Geoffrey and his family.147

Thus, the mystery of the Missing Years was born of the papal

mutation of witnesses who could have attested to a heretical

forfeiture which, in turn, would have directed historians

to the sindonic road from Constantinople to Languedoc.

|

Popes frequently prohibited - and still

prohibit - discussion of topics they find uncomfortable, including

the revenues generated by bogus relics.

|

| |

|

|

POSTSCRIPT--HERETICAL CUSTODIANS OF THE SHROUD: It

is entirely possible that, on three separate occasions, the

Shroud was in the possession of heretics. It has been argued

that, for at least one hundred and fifty years after the Resurrection,

the cloth was in the possession of Carpocratian Gnostics before

being brought to Edessa, during the reign of Abgar the Great

(177-212 A.D.), and remained there, in the possession of Gnostics,

for an additional lengthy period.148

In the eighth century, and as the result of an alleged loan

transaction, the cloth was given to Edessan Monophysites and/or

Jacobites and remained in their possession for a period of

almost two hundred and fifty years (circa 700-944 AD).149

Since this paper suggests that the cloth was in the possession

of Cathars

and their descendants for approximately one hundred and forty-five

years (1204-1349 AD), the cumulative heretical history of

the Shroud may exceed five centuries in length and constitute

more than twenty-five per cent of its present life.

|

|

NOTES

1. Ian Wilson hypothesized that this sydoine was

the Mandylion which could be traced back to before 50 AD Wilson,

pp. 128-130.

2. Wilson, p. 172. It should be noted that an earlier

period of "Missing Years" (from the Resurrection to 544 AD) also

remains unaccounted for, except in the hypotheses of sindonologists.

3. See Wilson, pp. 176-177.

4. Wilson, p. 169, citing Robert de Clari, The

Conquest of Constantinople, p. 112, trans. E.H. McNeal (New

York: Columbia University Press, 1936). "The Byzantine Emperor had

always relied on his relics to protect his throne and his city,

and in 1204 both were gravely threatened by the Frankish Crusaders".

Drews, p. 50.

5. See Wilson, pp. 112-124.

6. Wilson, p. 170.

7. Wilson, p. 140.

8. Wilson, pp. 140-141.

9. Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the

Roman Empire, Chapter 49, as cited in Wilson, p. 141.

10. Wilson, p. 144.

11. Wilson, pp. 147-148.

12. Currer-Briggs, pp. 126-127.

13. Warner, Vol. 1, pp. 14-15. Dualists in Constantinople

may have converted French crusaders to their heretical beliefs.

Sumption, p. 36. Crusaders, pilgrims and merchants were the likely

carriers of the heresy

to Western Europe. Wakefield, p. 29.

14. Sumption, pp. 17; 24. Baigent, p. 23.

15. Sumption, p. 39. The term "Cathar" is derived

from the Greek word for "purified" and was probably first used in

Northern Europe in about 1150. Sumption, p. 39. Wakefield, p. 30.

16. The Council branded Catharism a "damnable heresy".

Lea, p.118. Warner, Vol. 1, pp. 41-42.

17. Including a small military campaign. Wakefield,

pp. 82-86.

18. Hamilton, p. 115.

19. It is "incontrovertible that Bogomils and Cathars

had close relationships after the middle of the twelfth century".

Wakefield, p. 29.

20. Warner, Vol. 1, pp. 11; 14. Absolute dualists

held that there were two equal Gods, one good and one evil. Moderate

dualists believed in one God who created an evil demiurge who, in

turn, created the world. Paulicians were absolute dualists. The

Bogomils started as moderate dualists but, as the result of a schism

which likely occurred in the mid-twelfth century, split into factions

of absolute and moderate dualists. By 1172, the absolute dualists

had gained control over the Church of Constantinople. Hamilton,

pp. 115-124.

21. Warner, Vol. 1, pp. 15-16. The date of the Synod

was originally reported as 1167. See Hamilton, p. 116, f11. Reports

were spread that the Cathars

followed a pope headquartered in the Balkans. Wakefield, p. 32.

22. Warner, Vol. 2, p. 10. The Synod was held in

the village of St. Felix-de-Caraman. Wakefield, p. 31.

23. Hamilton, pp. 116-117.

24. Lea, pp. 119-120. Sumption, pp. 49-50. Warner,

Vol. 1, pp. 15-16.

25. Hamilton, p. 118. On a document located in the

archives of the Inquisition of Carcassonne,

it is noted: "This is a secret document of the heretics of Corcorezio,

brought from Bulgaria by Nazarius their Bishop, full of errors".

Warner, Vol. 1, p. 12.

26. The Council branded Catharism a "damnable heresy".

Lea, p.118. Warner, Vol. 1, pp. 41-42.

27. Baigent, p. 30. In addition, the Cathars employed

Bogomil scripture. See Wakefield, p. 35.

28. The Cathars' new leader, "Pope" Bartholemew,

created bishops, consecrated churches, made official visits, and

consulted with heretics throughout Languedoc. Warner, Vol. 2, pp.

109-110.

29. Innocent III employed the French to crusade,

in 1199, against Markward of Anweiler, Emperor Henry VI's representative

in Sicily, and, in 1202, against the Moslems. Strayer, pp. 45-47.

In Languedoc, he first attempted to control the heresy

by replacing local clergy and investing local legates with

the power to excommunicate, to interdict, and to remove clergy with

neither notice nor right of appeal. Sumption, pp. 60; 68.

30. Sumption, p. 67. Innocent referred to heresy

as a "hateful plague" and a "spreading canker", and called

heretics "vile wolves among the Lord's flock".

31. As noted, in approximately 1172, Nicetas had

converted the Cathars from moderate to absolute dualism. Thus, in

1204, they shared religious beliefs both with the Paulicians and

with the faction of the Bogomils which controlled the Church of

Constantinople. The Cathar ascetic lifestyle was modeled on the

Bogomils, who renounced worldly possessions, rather than the Paulicians,

who owned property, married, and fought as warriors. Hamilton, pp.

115-124.

32. Wilson, p. 173.

33. See Hamilton, p. 123. The dualists of Constantinople

had been permitted to have their own places of worship by the Byzantines.

Currer-Briggs, p. 140.

34. The Cathars rejected relics as devices through

which salvation could be procured. Lea, p. 93.

35. The Cathars also had sympathizers in the Knights

Templars (see the discussion on the Grail

appearance, infra., and endnote 48) and it is possible that

a Templar crusader pilfered the Shroud in Constantinople and sent

it to a Cathar friend or relative in Languedoc for their protection.

Currer-Briggs initially believed that Templars, for their own purposes,

may have brought the Shroud directly from Constantinople to Montpellier,

in Languedoc. Currer-Briggs, p. 92.

36. Esclarmonde once sent her sons on a raid of a

local monastery. Warner, Vol. 2, p. 11. During a disputation held

in Pamiers, she heckled the Church's representatives, provoking

a monk to exclaim: "Go away, woman, and spin at your distaff. It

is no business of yours to discuss matters such as these". Sumption,

p. 72. Warner, Vol. 2, p. 10. Oldenbourg, p. 60.

37. Warner, Vol. 2, pp. 10-11.

38. Lea, p. 138. Sumption, p. 60.

39. Warner, Vol. 2, p. 11. Perched 3,500 feet high

atop an almost sheer rock, Montsegur

was apparently a part of Esclarmonde's inheritance. Oldenbourg,

p. 317.

40. Oldenbourg, p. 317.

41. A retelling of the Edessa saga appears in Wilson,

pp. 137-138.

42. See, e.g., Currer-Briggs, pp. 1-29; 72-73.

43. See, e.g., Baigent, pp. 20; 34.

44. Maurin, pp. 60-61.

45. A conclusion reached by Prof. A.T. Hatto, a translator

of Parzival. See Currer-Briggs, p. 16.

46. Wolfram may have obtained some of his Grail/Shroud

information from his patron, the Landgrave Hermann of Thuringia,

the owner of a psalter containing one of the first-known illustrations

of the Crucifixion where three nails were used rather than four;

i.e., in a manner consistent with the evidence of the Shroud. See

Currer-Briggs, pp. 192-193 and the discussion on the Cathars' three-nail

Crucifix, infra.

47. For example, at precisely the time when the Shroud

remains hidden, Wolfram declares that the Grail

is not a fantasy, but, rather, a clue to something of immense importance

which has been concealed. See Currer-Briggs, p. 14. Wolfram also

links the Grail with the concept of resurrection. Wolfram, p. 124.

Currer-Briggs, pp. 14-15. Baigent, p. 266.

48. Currer-Briggs, p. 17. These and other coincidences

between certain details of Parzival and circumstances involving

the Cathars were first noted, in 1934, by a Nazi author, Otto Rahn

in Kreuzzug gegen den Graal. See Currer-Briggs, pp. 16-18.

49. Wolfram, p. 124. Currer-Briggs, p. 15.

50. The Cathars had developed a close relationship

with the Knights

Templar by donating vast tracts of land to the Temple Order

and by infiltrating its ranks to such a degree that, at the beginning

of the Albigensian Crusade, a significant proportion of high-ranking

Languedoc Templars derived from Cathar families. See Baigent, p.

46, citing E.-G. Leonard, Introduction au cartulaire manuscrit

du Temple, Paris, 1930, p. 76.

51. Baigent, p. 34; p. 62.

52. Baigent, p. 274. The work was entitled Der

Junge Titurel.

53. Warner, Vol. 2, pp. 10-11.

54. The cult of relics, such as the Passion and the

True Cross, formed the premise and genesis of the Fourth Crusade.

See Currer-Briggs, pp. 124-127.

55. The Pope proclaimed: "Let the strength of the

crown and the misery of war bring them back to the truth". Sumption,

pp. 75-76.

56. Sumption, p.15.

57. Sumption, p. 159.

58. Sumption, pp. 81-82. The Pope predicted that,

if Raymond did not come to the aid of the heretics, "nothing should

be easier than to finish them off" and counseled that, when the

Cathars had been eliminated, the crusade should turn its attention

to the Count

of Toulouse. See, Oldenbourg, p. 15.

59. Wakefield, p. 97. Once Raymond had declared himself

an obedient son of the Church and submissive to any condition which

the Pope might impose upon him, he literally destroyed half of the

raison d'etre of the Crusade. Oldenbourg, p. 14.

60. Currer-Briggs claims that, in an illustration

appearing in a psalter dated to 1211-1212 and owned by the Landgrave

Hermann of Thuringia, Christ is first portrayed as being pierced

by three nails, with one nail driven through both feet, consistent

with what Currer-Briggs believes to be the evidence of the Shroud.

Currer-Briggs, pp. 191-192. It is an interesting coincidence that

this depiction of the Crucifixion appears in the prayerbook of the

patron of Wolfram von Eschenbach whose Grail

legend seems to place the Shroud in Languedoc between 1205 and 1207.

61. Currer-Briggs, p. 192.

62. This was an "unconventional" form of the Crucifixion.

Lea, pp. 102-103. Apparently, the hands were nailed above the head

and parallel to the body, with either one hand nailed above (but

not overlapping) the other or with one hand nailed to each side

of the upright beam.

63. Sumption, 48-49.

64. See, e.g., Barbet, Pierre, Proof of the Authenticity

of the Shroud in the Bloodstains: Part II, Shroud Spectrum International,

No. 23, p. 10. Currer-Briggs, p. 192.

65. On June 25, 1218, the Crusade leader, Simon de

Montfort was killed and was succeeded by his son, Amaury who served

in that capacity until January 14, 1224 when he made peace with

the Counts

of Toulouse and Foix.

66. Joinville (Trans. Joan Evans), p. 15. The precise

date and circumstances of the invitation remain unknown. Guilhabert

de Castres, who was probably among the privileged few to have viewed

the Shroud, was in Castelnaudary during Amaury's eight-month siege

of the city in 1220-1221 and escaped to continue his missionary

work in the surrounding areas. Strayer, pp. 119-120. Sumption, p.

228.

67. Oldenbourg, p. 36.

68. Warner, Vol. 1, p. 31.

69. Lea, p. 93.

70. Lea, p. 94.

71. There is, however, one uncorroborated account

of a Cathar Easter Day celebration in which the participants profess

their belief that consecrated bread and wine is the body and blood

of Christ. See Warner, Vol. 1, pp. 80-82.

72. Sumption, p. 234.

73. Warner, Vol. 1, pp. 73-74.

74. Lea, pp. 103-104.

75. Joinville (Trans. Rene Hague), pp. 5-6.

76. Including the future Louis X, who was presented

with the book in 1309. Joinville (Trans. Rene Hague), p. 9.

77. Meanwhile, at the Fourth Lateran Council, Esclarmonde's

brother, the Count, denounced her as an evil and sinful woman and

the Catholic Bishop of Toulouse railed that she had perverted many.

Oldenbourg, p. 182. Warner, Vol. 2, p. 85. The Count maintained

that he was not responsible for his sister and that he had no authority

over Montsegur.

"Am I to be ruined for my sister's sins?", he asked. Sumption, p.

180.

78. Guilhabert was appointed Cathar Bishop of Toulouse

in 1208. Madaule, p. 51; Wakefield, p. 169.

79. Sumption, p. 228.

80. Sumption, p. 228. Guilhabert's missionary work

has been favorably compared with that of the Apostles. See Madaule,

p. 51.

81. Sumption, p. 237.

82. Wakefield, p. 169.

83. Oldenbourg, p. 363.

84. Warner, Vol. 2, p. 152.

85. Oldenbourg, p. 317. Sumption, p. 236.

86. Montsegur

remained untouched even as surrounding areas were captured by crusaders

in 1209 and 1212. See Sumption, p. 236. Oldenbourg, p. 317f.

87. Baigent, pp. 30-31.

88. Oldenbourg, p. 353. Baigent, pp. 31; 35.

89. Oldenbourg, pp. 355-356.

90. The request was made, apparently, for some religious

purpose. Sumption, p. 240.

91. Baigent, p. 33. Easter was the most important

celebration of the Cathar religious year. Warner, Vol. 1, p. 81.

92. Sumption, p. 240. The victims included Raymond

de Perella's wife, daughter, and mother-in-law. Oldenbourg, pp.

362-363.

93. Oldenbourg, p. 361.

94. Sumption, p. 241. Baigent, p. 32.

95. Baigent, p. 32. Some survivors of Montsegur

claimed that these men were sent to retrieve the treasure which

had been removed in January. Oldenbourg, p. 362.

96. It is rather ironic that the three most important

years in the palladian history of the Shroud involve "forty-fours";

i.e., the Shroud saved Edessa in 544, it was taken from Edessa to

protect Constantinople in 944, and it failed to rescue Montsegur

in 1244.

97. In 1244, Easter fell on April 3.

98. Madaule, p. 136.

99. The Auteris lived in Ax-les-Thermes and had been

heretics since 1230. Madaule, p. 136.

100. As late as the mid-1270's, the nobility of Aragon

sought support against the King of France from Cathars hiding in

the Pyrenees. Shneidman, p. 321. From 1298 to 1309, the Cathars

hid an itinerant Perfect in the southern highlands of Languedoc.

Sumption, pp. 242-243.

101. In 1299, Cathars were arrested at Albi and in

1310, the Inquisition of Toulouse extracted Cathar confessions.

Lea, p. 97.

102. Warner, Vol. 2, p. 209.

103. Warner, Vol. 2, p. 214.

104. Warner, Vol. 2, pp. 214-216.

105. Sumption, p. 243. Madaule, pp. 137-138.

106. Madaule, p. 137.

107. Warner, Vol. 2, p. 216.

108. Strayer, p. 162.

109. Parenthetically, a Cathar-based Shroud biography

which ends in the years after Montsegur

still lends itself to a subsequent

Templar possession and Geoffrey's acquisition of the relic through

his family's putative Templar connections. The Temple Order, infiltrated

by Cathars, provided safe havens for Cathar refugees who may have

given the Shroud to their Templar protectors. See Baigent, p. 46.

110. Warner, Vol. 2, pp. 145-146; p. 174.

111. In 1215, the Fourth Lateran Council relegated

punishment of condemned heretics to the State which was expected

to confiscate their goods. Warner, Vol. 2, p. 90. In 1228, Louis

IX ordered his bailiffs to seize the goods of the excommunicated.

Warner, Vol. 2, pp. 194-195. The Statutes of Toulouse, promulgated

in 1233, provided that all goods found in a heretic's house or hiding

place were to be confiscated and that all heretical inheritances

were to be forfeited unless the children could prove their own orthodoxy.In

1243, Pope Innocent IV approved the twelve statutes of Emperor Frederick

which consigned condemned heretics to the State for punishment,

treated heretical sympathizers as if they themselves were heretics,

and deprived the heirs and successors of both heretics and their

sympathizers of all temporal benefits. Warner, Vol. 2, pp. 153-154.

In Toulouse, all forfeited real property was divided between the

king and the bishop and all forfeited personal property belonged

exclusively to the crown. Warner, Vol. 2, pp. 194-195.

112. Even up in the mountains, a careless word could

lead to imprisonment or persecution by the Inquisition. See Le Roy

Ladurie, pp. 13-14.

113. Gottfried, p. 42.

114. This according to the "thoroughly reliable"

Gilles de Massis. Nohl, p. 40.

115. Gottfried, p. 49.

116. Nohl, p. 40.

117. Gottfried, p. 49.

118. Nohl, p. 40.

119. Gottfried, 50.

120. Gottfried, p. 50.

121. Nohl, p. 40.

122. Gottfried, p. 50-51. In Montaillou, one of the

last centers of Catharism, only half of the population survived

the catastrophes of the second part of the fourteenth century. Le

Roy Ladurie, p. 3.

123. Nohl, p. 37.

124. Gottfried, p. 53.

125. Wilson, p. 86.

126. A change in Geoffrey's burial plans appears

to pinpoint this period as the time frame for his acquisition of

the Shroud. See Crispino, Dorothy, Why Did Geoffroy deCharny

Change His Mind?, Shroud Spectrum International, Vol. 1, pp.

30-31.

127. Geoffrey fought at Calais in 1349 and 1351;

at Picardy in 1353; at Normandy in 1354; and at Breteuil in 1356.

See Crispino, Dorothy, Why Did Geoffroy deCharny Change His Mind,

Shroud Spectrum International, No. 1, pp. 28-29.

128. Least likely is a gift from the king. See Wilson,

p. 193.

129. Wilson, p. 196.

130. Wilson, p. 87.

131. Wilson, p. 192.

132. Froissart, p. 129.

133. Crispino, Dorothy, Geoffroy de Charny in

Paris, Shroud Spectrum International, No. 24, Sept. 1987, p.

13. The grant is preserved in the Archives Nationales JJ77 #395,

folio 245 and is hand-copied in the Wuenschel Collection.

134. In these three areas of Languedoc, Geoffrey

probably employed bailiffs to represent his interests. See Crispino,

Dorothy, Poor Geoffrey, Shroud Spectrum International, Spicilegium,

1996, p. 24. A bailiff (bayle) was generally a non-native

who acted as mayor, chief of police, judge, tax collector, and army

mobilization officer all in one. See Wilson, p. 204.

135. Le Roy Ladurie, p. 11.

136. Even while imprisoned, Geoffrey would have readily

learned of his good fortune since his servants were travelling between

London and Paris in connection with raising a ransom for his release

and Geoffrey himself was released on parole in September of 1350

to attend the wedding of King John in Paris. Crispino, Dorothy,

To Know the Truth, Shroud Spectrum International, No. 28/29,

p. 34.

137. See Wilson, p. 90.

138. Wilson, p. 87. Wilson believes this something

to be the Shroud's hypothetical Templar

history and the memory of that Order's "savage downfall". Wilson,

p. 195.

139. In all likelihood, Geoffrey made his report

to Clement VI, who became Pope in 1342 since Geoffrey would have

probably filed his petition subsequent to his release from prison

in June of 1351. Pope Clement VI died in December of 1352 and construction

of the Lirey church took place between February and June of 1353,

during the papacy of Innocent VI, who reigned until 1362. Both Clement

VI and Innocent VI were French.

140. The documents have not yet been found, but certainly

must exist. Crispino, Dorothy, Why Did Geoffroy deCharny Change

His Mind?, Shroud Spectrum International, No. 1, p. 32. Church

approval was sought in 1389 by Geoffrey's son who obtained it directly

from the Pope's French legate, Cardinal de Thury, thereby circumventing

Bishop D'Arcis of Troyes. Wilson, Appendix B, pp. 267-268.

141. At least as reported by Pierre D'Arcis in his

draft memorandum of approximately 1389. See, Wilson, Appendix B,

p. 267.

142. Geoffrey's son said only that it had been graciously

given to his father, and his granddaughter stated merely that Geoffrey

had acquired it. Crispino, Dorothy, Why Did Geoffroy deCharny

Change His Mind?, Shroud Spectrum International, No. 1, p. 29.

Crispino, Dorothy, To Know the Truth, Shroud Spectrum International,

No. 28/29, pp. 30-31.

143. See, e.g., Bonnet-Eymard, Bruno, Study of

Original Documents of the Archives of the Diocese of Troyes in France

with Particular Reference to the Memorandum of Pierre D'Arcis,

Shroud News, No. 68, pp. 8-9.

144. Wilson, Appendix B, pp. 266-272.

145. The Inquisition's Piedmontese trials were held

in 1388. See, Lea, p. 96f.

146. Clement was the nephew of Geoffrey's widow,

Jeanne de Vergy, through her second marriage. Wilson, p. 206.

147. Wilson, pp. 209-210. Wilson concluded that Pope

Clement VII knew of the Shroud's Missing Years biography (albeit

Templar-based) and suppressed the truth both for political reasons

and in "a pious attempt to introduce a genuine relic for public

veneration". Wilson, pp. 208-210.

148. This argument claims that the image on the Shroud

is manmade. See, Drews, pp. 75-96.

149. The relic was pawned to a Monophysite, Athanasius

bar Gumayer, and was deposited into the Jacobite Church of the Mother

of God in Edessa. See Wilson, pp. 149; 254, citing J.B. Segal's,

Edessa the Blessed City.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baigent, Michael, Leigh, Richard, and Lincoln, Henry

III, Holy Blood, Holy Grail, Delacorte Press (New York, 1982).

Currer-Briggs, Noel, The Shroud and the Grail,

Weidenfeld and Nicolson (London, 1987).

Drews, Robert, In Search of the Shroud of Turin,

Rowman & Allanheld (Totowa, 1984).

Froissart, Jean, Chronicles (Trans. Geoffrey

Brereton), Penguin Books.

Gottfried, Robert S., The Black Death, The

Free Press (New York, 1983).

Hamilton, Bernard, Monastic Reform, Catharism

and the Crusades (900-1300), Variorum Reprints (London 1979).

Joinville, Jean de, The History of St. Louis

(Trans. Joan Evans),

Oxford University Press (London, New York and Toronto,

1938).

Joinville, Jean de, The Life of St. Louis,

(Trans. Rene Hague), Sheed and Ward (New York, 1955).

Lea, Henry Charles, A History of the Inquisition

of the Middle Ages, The Macmillan Company (New York, 1908).

Le Roy Ladurie, Emmanuel, Montaillou, The Promised

Land of Error (Trans. Barbara Bray), George Braziller, Inc.

(New York, 1978).

Madaule, Jacques, The Albigensian Crusade

(Trans. Barbara Wall), Fordham University Press (New York, 1967).

Maurin, Krystel, Les Esclarmonde, Editions

Privat (Toulouse 1995).

Nohl, Johannes, The Black Death, A Chronicle of

the Plague (Trans.

C.H. Clarke), Harper & Rowe (New York and Evanston,

1969).

Oldenbourg, Zoe, Massacre at Montsegur (Trans.

Peter Green), Pantheon Books (New York, 1961).

Shneidman, J. Lee, The Rise of the Aragonese-Catalan

Empire, 1200- 1350, New York University Press (New York, 1970).

Sumption, Jonathan, The Albigensian Crusade,

Faber & Faber (London and Boston, 1978).

Strayer, Joseph R., The Albigensian Crusades,

The Dial Press (New York, 1971).

Wakefield, Walter L., Heresy, Crusade and Inquisition

in Southern France, 1100-1250, University of California Press

(Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1974).

Warner, H.J., The Albigensian Heresy, Russell

& Russell (New York, 1967).

Wilson, Ian, The Shroud of Turin, The Burial Cloth

of Jesus Christ?, Image Books (Garden City, N.Y., 1979).

Wolfram, von Eschenbach, Parzival (Trans.

Andre Lefevere), The Continuum Publishing Company (New York, 1991).

History of the Shroud of Turin

Possible history before the 14th century: The Image of Edessa

According

to the Gospel of John (John 20:5-7), the Apostle Peter and the "beloved

disciple" entered the sepulchre of Jesus, and found the "linen

clothes" that had wrapped his body and "the napkin, that

was about his head." According

to the Gospel of John (John 20:5-7), the Apostle Peter and the "beloved

disciple" entered the sepulchre of Jesus, and found the "linen

clothes" that had wrapped his body and "the napkin, that

was about his head."

There are numerous reports of Jesus' burial shroud, or an image

of his head, of unknown origin, being venerated in various locations

before the fourteenth century. None of these reports has been connected

with certainty to the cloth held in the Turin cathedral. Except

for the Image of Edessa, none of the reports of these (up to 43)

different "true shrouds" was known to mention an image

of a full body.

The Image of Edessa was reported to contain the image of the face

of Jesus and its existence is reported since the sixth century.

Some have suggested a connection between the Shroud of Turin and

the Image of Edessa. No legend connected with that image suggests

that it contained the image of a beaten and bloody Jesus. It was

said to be an image transferred by Jesus to the cloth in life. This

image is generally described as depicting only the face of Jesus,

not the entire body. Proponents of the theory that the Edessa image

was actually the shroud posit that it was always folded in such

a way as to show only the face.

John Damascene mentions the image in his anti-iconoclastic work

On Holy Images, describing the Edessa image as being a "strip,"

or oblong cloth, rather than a square, as other accounts of the

Edessa cloth hold. However, in his description, John still speaks

of the image of Jesus' face when he was alive. On the occasion of

the transfer of the cloth to Constantinople in 944, Gregory Referendarius,

archdeacon of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, preached a sermon

about the artifact. This was rediscovered in the Vatican Archives

and translated by Mark Guscin in 2004. This sermon says that this

Edessa cloth contained not only the face, but a full-length image,

which was believed to be of Jesus. The sermon also mentions bloodstains

from a wound in the side. Other documents have since been found

in the Vatican library and the University of Leiden, Netherlands,

confirming this impression.

In 1203, a Crusader knight named Robert de Clari claims to have

seen the cloth in Constantinople: "Where there was the Shroud

in which our Lord had been wrapped, which every Friday raised itself

upright so one could see the figure of our Lord on it."

After the Fourth Crusade, in 1205, the following letter was sent

by Theodore Angelos, a nephew of one of three Byzantine Emperors

who were deposed during the Fourth Crusade, to Pope Innocent III

protesting the attack on the capital. From the document, dated 1

August 1205:

"The Venetians partitioned the treasures of gold, silver,

and ivory while the French did the same with the relics of the

saints and the most sacred of all, the linen in which our Lord

Jesus Christ was wrapped after his death and before the resurrection.

We know that the sacred objects are preserved by their predators

in Venice, in France, and in other places, the sacred linen in

Athens."

(Codex Chartularium Culisanense, fol. CXXVI (copia), National

Library Palermo)

Unless it is the Shroud of Turin, then the location of the Image

of Edessa since the 13th century is unknown.

Some historians suggest that the shroud was captured by the knight

Otto de la Roche who became Duke of Athens, but that he soon relinquished

it to the Knights

Templar.

It was subsequently taken to France, where the first known keeper

of the Turin Shroud had links both to the Templars

as well the descendants of Otto. Some speculate that the shroud

could have been a major part of the famed 'Templar treasure' that

treasure hunters still seek today.

The association with the Templars seems to be based on a coincidence

of family names, especially since the Templars were a celibate order,

and so unlikely to have (especially acknowledged) children. However,

the location of the Shroud in the 13th-14th centuries is interesting,

since the Frankish (French) contingent in 4th Crusade, which resulted

in the sack of Constantinople, was led by Tibaut of Champagne. Lirey,

the first known location of the Turin Shroud, is located in the

territory of this Count.

14th century

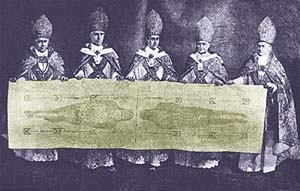

The known provenance of the cloth now stored in Turin dates to

1357, when the widow of the French knight Geoffroi de Charny (said

to be a descendant of Templar

Geoffroy de Charney who was burned at the stake with Jacques de

Molay) had it displayed in a church at Lirey, France (diocese of

Troyes).

During the fourteenth century, the shroud was often publicly exposed,

though not continuously, because the bishop of Troyes, Henri de

Poitiers, had prohibited veneration of the image. Thirty-two years

after this pronouncement, the image was displayed again, and King

Charles VI of France ordered its removal to Troyes, citing the impropriety

of the image. Sheriffs were unable to carry out the order.

In 1389, the image was denounced as a fraud by Bishop Pierre D'Arcis

in a letter to the Avignon Pope (now Antipope) Clement VII. Despite

the pronouncement of Bishop D'Arcis, Clement VII (first "antipope"

of the Western Schism) prescribed indulgences for pilgrimages to

the shroud, so that veneration continued, though the shroud was

not permitted to be styled the "True Shroud."

Alternative 14th century origins

The Second Messiah by Christopher Knight and Robert Lomas

argues that the Shroud's image is that of the final Knights

Templar leader, Jacques de Molay.

On Friday, 13 October 1307, the Templars

were arrested by Philip the Fair under the authority of Pope Clement

V. De Molay was nailed to a door and tortured, and his almost comatose

body was wrapped in a cloth and left for 30 hours to recover. According

to the hypothesis of Dr. Alan A. Mills in his article "Image

formation on the Shroud of Turin," in Interdisciplinary Science

Reviews, 1995, vol. 20 No. 4, pp 319–326, convection currents

from the lactic acid in de Molay's perspiration created the image.

The image corresponds to what would have been produced by a volatile

chemical if the intensity of the color change were inversely proportional

to the distance of the cloth from the body, and the slightly bent

position accounts for the extension of the hands onto the thighs,

something not possible if the body had been laid flat.

Further, according to Knight and Lomas, de Molay, and co-accused

Geoffroy de Charney, were then cared for by brother Jean de Charney,

whose family retained the shroud after de Molay's execution on 19

March 1314.

15th century

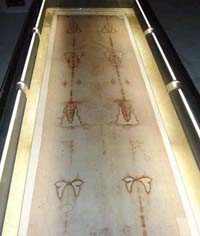

In

1418, Humbert of Villersexel, Count de la Roche, Lord of Saint-Hippolyte-sur-Doubs,

moved the shroud to his castle at Montfort, Doubs, to provide protection

against criminal bands, after he married Charny's granddaughter

Margaret. It was later moved to Saint-Hippolyte-sur-Doubs. After

Humbert's death, canons of Lirey fought through the courts to force

the widow to return the cloth, but the parliament of Dole and the

Court of Besançon left it to the widow, who traveled with

the shroud to various expositions, notably in Liège and Geneva. In

1418, Humbert of Villersexel, Count de la Roche, Lord of Saint-Hippolyte-sur-Doubs,

moved the shroud to his castle at Montfort, Doubs, to provide protection

against criminal bands, after he married Charny's granddaughter

Margaret. It was later moved to Saint-Hippolyte-sur-Doubs. After

Humbert's death, canons of Lirey fought through the courts to force

the widow to return the cloth, but the parliament of Dole and the

Court of Besançon left it to the widow, who traveled with

the shroud to various expositions, notably in Liège and Geneva.

The widow sold the shroud in exchange for a castle in Varambon,

France in 1453. Louis of Savoy, the new owner, stored it in his

capital at Chambery in the newly built Saint-Chapelle, which Pope

Paul II shortly thereafter raised to the dignity of a collegiate

church. In 1464, the duke agreed to pay an annual fee to the Lirey

canons in exchange for their dropping claims of ownership of the

cloth.

Beginning in 1471, the shroud was moved between many cities of

Europe, being housed briefly in Vercelli, Turin, Ivrea, Susa, Chambery,

Avigliana, Rivoli, and Pinerolo. A description of the cloth by two

sacristans of the Sainte-Chapelle from around this time noted that

it was stored in a reliquary: "enveloped in a red silk drape,

and kept in a case covered with crimson velours, decorated with

silver-gilt nails, and locked with a golden key."

16th century to present

In

1532, the shroud suffered damage from a fire in the chapel where

it was stored. A drop of molten silver from the reliquary produced

a symmetrically placed mark through the layers of the folded cloth.

Poor Clare Nuns attempted to repair this damage with patches. Some

have suggested that there was also water damage from the extinguishing

of the fire. However, there is some evidence that the watermarks

were made by condensation in the bottom of a burial jar in which

the folded shroud may have been kept at some point. In 1578, the

shroud arrived again at its current location in Turin. It was the

property of the House of Savoy until 1983, when it was given to

the Holy See. In

1532, the shroud suffered damage from a fire in the chapel where

it was stored. A drop of molten silver from the reliquary produced

a symmetrically placed mark through the layers of the folded cloth.

Poor Clare Nuns attempted to repair this damage with patches. Some

have suggested that there was also water damage from the extinguishing

of the fire. However, there is some evidence that the watermarks

were made by condensation in the bottom of a burial jar in which

the folded shroud may have been kept at some point. In 1578, the

shroud arrived again at its current location in Turin. It was the

property of the House of Savoy until 1983, when it was given to

the Holy See.

In 1988, the Holy See agreed to a radiocarbon dating of the relic,

for which a small piece from a corner of the shroud was removed,

divided, and sent to laboratories. Another fire threatened the shroud

on 11 April 1997, but a fireman was able to remove it from its heavily

protected display case and prevent further damage.

In 2002, the Holy See had the shroud restored. The cloth backing

and thirty patches were removed. This made it possible to photograph

and scan the reverse side of the cloth, which had been hidden from

view.

Using sophisticated mathematical and optical techniques, a part-image

of the body was found on the back of the shroud in 2004. Italian

scientists had exposed the faint imprint of the face and hands of

the figure. The most recent public exhibition of the Shroud was

in 2000 for the Great Jubilee. The next scheduled exhibition is

in 2025.

Theories of how the image on the Shroud was formed

The image on the cloth has many peculiar and closely studied characteristics,

for example, it is entirely superficial, not penetrating into the

cloth fibers under the surface, so that the flax and cotton fibers

are not colored; the image yarn is composed of discolored fibers

placed side by side with non-discolored fibers so many striations

appear. Thus the cloth is not simply dyed, though many other explanations,

natural and otherwise, have been suggested for the image formation.

Alone among published researchers, McCrone believed the entire image

to be composed of pigment - no one disputes that some of it, notably

the "blood" is actually a pigment.

Miraculous formation

Believers have hypothesized that the image on the shroud was produced

by a side effect of the Resurrection of Jesus.

Maillard reaction theory

The Maillard reaction is a form of non-enzymatic browning involving

an amino acid and a reducing sugar. The cellulose fibers of the

shroud are coated with a thin carbohydrate layer of starch fractions,

various sugars, and other impurities. In a paper entitled "The

Shroud of Turin: an amino-carbonyl reaction may explain the image

formation," R.N. Rogers and A. Arnoldi propose that amines

from a recently deceased human body may have undergone Maillard

reactions with this carbohydrate layer within a reasonable period

of time, before liquid decomposition products stained or damaged

the cloth. The gases produced by a dead body are extremely reactive

chemically and within a few hours, in an environment such as a tomb,

a body starts to produce heavier amines in its tissues such as putrescine

and cadaverine. This raises questions as to why the images (both

ventral and dorsal views) are so photorealistic, and why they were

not destroyed by later decomposition products. Removal of the cloth

from the body within a short enough time frame would prevent exposure

to these later decomposition products.

Auto-oxidation

Christopher Knight and Robert Lomas (1997) claim that the image

on the shroud is that of Jacques de Molay, the last Grand Master

of the Order of the Knights

Templar, arrested for heresy

at the Paris Temple by Philip IV of France on 13 October 1307.

De Molay suffered torture under the auspices of the Chief Inquisitor

of France, William Imbert. His arms and legs were nailed, possibly

to a large wooden door. According to Knight and Lomas, after the

torture De Molay was laid on a piece of cloth on a soft bed; the

excess section of the cloth was lifted over his head to cover his

front and he was left, perhaps in a coma, for perhaps 30 hours.

They claim that the use of a shroud is explained by the Paris Temple

keeping shrouds for ceremonial purposes.

De Molay survived the torture but was burned at the stake on 19

March 1314 together with Geoffroy de Charney, Templar

preceptor of Normandy. De Charney's grandson was Jean de Charney

who died at the battle of Poitiers. After his death, his widow,

Jeanne de Vergy, purportedly found the shroud in his possession

and had it displayed at a church in Lirey.

Knight and Lomas base their argument partly on the 1988 radiocarbon

dating and Mills' 1995 research about a chemical reaction called