Languedoc Topics

Mysteries of the Languedoc

The Knights Templar

|

How and why they were founded, their links with the Temple of Solomon and modern Freemasons. Why their Order was destroyed in the Fourteenth century.

They were essentially Cistercian monks following the rule of St Benedict, and also warrior knights - the combination was not regarded as odd during the Middle Ages - or indeed until the advent of the secular age. They were famed throughout Christendom for many reasons. Their independence from the normal Church hierarchy invited the hostility of bishops. Their fighting prowess attracted ambitious noblemen and wealthy patrons. Their ever growing wealth invited the envy of kings. Their friendship with Moslem hashashin created a scandal. Their military record was exceptional.

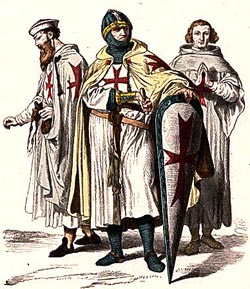

Endorsed by the Roman Catholic Church in 1128, the Order became a favoured charity across Europe and grew rapidly in membership and power. Templar knights, in white mantles each with a red cross, were among the best fighting units of the Crusades.

The abrupt disappearance of a major part of the European infrastructure gave rise to speculation and legends, which have kept the "Templar" name alive until the present. There is virtually no evidence that the Templars were guilty of any of the great crimes they were accused of, though their is some circumstantial suggestions that they followed ideas from the time of Jesus - possibly even recognising John the Baptist as the Messiah. Their dissolution, like the dispossession of the Jews during the same period, was clearly motivated not by their sins, crimes or heresy but by the French King's desire to seize their huge wealth.

|

After the First Crusade captured Jerusalem in 1099, many European pilgrims travelled to visit what they referred to as the Holy Places. Although the city of Jerusalem was under relatively secure control, the rest of the Outremer was not. Bandits abounded, and pilgrims were sometimes attacked, as they made the journey from Jaffa on the Mediterranean coast towards Jerusalem.

Around 1119, two veterans of the First Crusade, a French knight called Hugues de Payens and his relative Godfrey de Saint-Omer, proposed the creation of a monastic order for the protection of the pilgrims. King Baldwin II of Jerusalem agreed to their request, and gave them space for a headquarters on the Temple Mount, in the Al Aqsa Mosque. The Temple Mount had a mystique, because it was above the ruins of the Temple of Solomon. The Crusaders referred to the Mosque as Solomon's Temple, and it was from this location that the Order took the name of Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon, or "Templar" knights. The Order, initially with about nine knights, had few financial resources and relied on donations to survive. Their emblem was of two knights riding on a single horse, emphasising the Order's poverty.

The Templars' impoverished status did not last long. They had a powerful advocate in Bernard of Clairvaux, a leading Church figure and a nephew of one of the founding knights. He spoke and wrote persuasively on their behalf, and in 1129 at the Council of Troyes, the Order was officially endorsed by the Church. With this formal blessing, the Templars became a favoured organisation across western Christendom, receiving money, land and noble-born sons from families who were eager to help with the fight in the Holy Land.

Another major benefit came in 1139, when Pope Innocent II's papal bull Omne datum optimum exempted the Order from obedience to local laws. This ruling meant that the Templars could pass freely through all borders, were not required to pay any taxes, and were exempt from all authority except that of the Pope.

With a clear mission and ever increasing resources, the Order grew rapidly. Templars were often the advance force in key battles of the Crusades, as the knights on their heavily armed warhorses would set out to gallop at the enemy to break their lines. They were the mobile artillery - the tanks - of their day.

Although the primary mission of the Order was military, relatively few members were combatants. Others acted in support positions to assist the knights and to manage their vast financial infrastructure. Like other monastic orders, members were sworn to individual poverty, but the order itself grew fabulously wealthy. In 1150 the Order began generating letters of credit for pilgrims journeying to the Holy Land: pilgrims deposited their valuables with a local Templar preceptory before embarking, received an encrypted document indicating the value of their deposit, then used that document upon arrival in the Holy Land to claim their funds. This innovative arrangement may have been the first formal system to support the use of what were essentially cheques. It also improved the safety of pilgrims by making them less attractive targets for thieves, and also contributed to the Templar coffers especially since a substantial proportion of deposits would never be reclaimed.

![]() The

Templar established financial networks across the whole of Christendom.

They acquired large tracts of land, both in Europe and the Middle

East; they bought and managed farms and vineyards; they built churches

and castles; they were involved in manufacturing, import and export;

they had their own fleet of ships; and at one point they even owned

the island of Cyprus. The Templar Order was in many ways the world's

first multinational corporation.

The

Templar established financial networks across the whole of Christendom.

They acquired large tracts of land, both in Europe and the Middle

East; they bought and managed farms and vineyards; they built churches

and castles; they were involved in manufacturing, import and export;

they had their own fleet of ships; and at one point they even owned

the island of Cyprus. The Templar Order was in many ways the world's

first multinational corporation.

In the mid-1100s, the tide began to turn in the Crusades. The Muslim

world had become united under effective leaders such as Saladin,

and dissension arose among Christian factions in and concerning

the Holy Land. Knights Templar were constantly at odds with other

Christian orders, the Knights Hospitaller and the Teutonic Knights.

Decades of internecine feuds had weakened Christian positions, both

politically and militarily. After the Templars were involved in

several unsuccessful campaigns, including the pivotal Battle of

the Horns of Hattin, Jerusalem was captured by Saladin's forces

in 1187. The Crusaders retook the city in 1229, without Templar

assistance, but held it only briefly. In 1244, the Khwarezmi Turks

recaptured Jerusalem, and the city did not return to Western control

until 1917 - when the British took it from the Ottoman Turks.

The Templars were forced to relocate their headquarters to other cities in the north, such as the seaport of Acre, which they held for the next century. But they lost that too in 1291, followed by their last mainland strongholds, Tortosa (then in the County of Tripoli, modern Syria), and Atlit. Their headquarters moved to Limassol, Cyprus, with a garrison on Arwad Island, off the coast from Tortosa. In 1300, there was an attempt to engage in co-ordinated military efforts with the Mongols via a new invasion force at Arwad. In September 1302 the Templars were defeated by a Mamluk fleet in the Siege of Arwad, losing their last foothold in the Holy Land.

The Order's military mission having failed, European support for

the organisation began to dwindle. Over the two hundred years of

their existence, the Templars had become a part of European daily

life. Hundreds of Templar Houses dotted around Europe, gave them

a widespread presence at the local level. Templars still managed

many businesses, and many Europeans had daily contact with the Templar

network, for instance working at a Templar farm or vineyard, or

using the Order as a bank in which to store personal valuables.

The Order continued to be independent of local government, a source

of irritation to bishops everywhere. It had a standing army that

could pass freely through all borders, but that no longer had a

mission. This situation heightened tensions with European nobility,

especially as the Templars were indicating an interest in founding

their own monastic state, as the Teutonic Knights had done in Prussia,

and the Knights Hospitaller were doing with Rhodes.

Organisation

The Templars were a monastic order, based on Bernard's Cistercian Order. The organisational structure had a strong chain of authority. Each country with a major Templar presence (France, England, Aragon, Portugal, Poitou, Apulia, Jerusalem, Tripoli, Antioch, Anjou, and Hungary) had a Master of the Order for the Templars in that region. All of them were subject to the Grand Master, always a French knight, appointed for life, who oversaw the Order's military efforts in the East and their financial holdings in the West. No precise numbers exist, but it is likely that at the Order's peak there were between 15,000 and 20,000 Templars, of whom about a tenth were knights.

Bernard de Clairvaux and Hugues de Payens devised the code of behaviour for the Templar Order, known to modern historians as the Latin Rule. Its 72 clauses defined the ideal behaviour for the Knights, such as the types of robes they were to wear and how many horses they could have. Knights were to take their meals in silence, eat meat no more than three times per week, and were not to have physical contact of any kind with women, even members of their own family. As the Order grew, more guidelines were added, and the original list of 72 clauses expanded to several hundred in its final form.

![]() There

was a threefold division of the ranks of the Templars: the aristocratic

knights, the lower-born sergeants, and the clergy.

There

was a threefold division of the ranks of the Templars: the aristocratic

knights, the lower-born sergeants, and the clergy.

- Knights were required to be of knightly descent, and to wear white mantles. They were equipped as heavy cavalry, with three or four horses, and one or two squires. Squires were generally not members of the Order, but were instead outsiders who were hired for a set period of time. Knights wore white robes with a red cross, and a white mantle;

- Beneath the knights in the Order and drawn from lower social strata were the sergeants. They were either equipped as light cavalry with a single horse, or served in other ways such as administering the property of the Order or performing menial tasks and trades. Sergeants wore a black tunic with a red cross on front and back, and a black or brown mantle.

- Chaplains, constituting a third Templar class, were ordained priests who saw to the Templars' spiritual needs.

The white mantle was assigned to the Templars at the Council of Troyes in 1129, and the cross was most probably added to their robes at the launch of the Second Crusade in 1147, when Pope Eugenius III, King Louis VII of France, and many other notables attended a meeting of the French Templars at their headquarters near Paris. According to their Rule, the knights were to wear the white mantle at all times, even being forbidden to eat or drink unless they were wearing it.

Initiation, known as Reception (receptio) into the Order, was a profound commitment and involved a solemn ceremony. Outsiders were discouraged from attending the ceremony, an fact that excited the suspicions of Inquisitors during the later trials.

New members had to sign over all of their wealth and goods to the Order and take vows of poverty, chastity, piety, and obedience just like other monks. Most brothers joined for life, although some were allowed to join for a set period.

The red cross that the Templars wore on their robes was a symbol of martyrdom, and Popes repeatedly told them that to die in combat was a great honour that assured a place in heaven. There was a rule that the warriors of the Order should never surrender unless the Templar flag had fallen, and even then they were first to try to regroup with another of the Christian orders. Only after all flags had fallen were they allowed to leave the battlefield. This uncompromising principle, along with their reputation for courage, their excellent training, and their heavy armament, made the Monastic Orders the most feared combat forces in medieval times. One consequence was that the Moslem armies, who generally took Christian knights prisoner and ransomed them back, usually executed captured Templars and Hospitalers. Grand Master Gérard de Ridefort was beheaded by Saladin in 1189 at the Siege of Acre.

Starting with founder Hugues de Payens in 1118–1119, the Order's highest office was that of Grand Master, a position which was held for life, though this could mean a very short tenure. All but two of the Grand Masters died in office, and several died during military campaigns.

The Grand Master oversaw all of the operations of the Order, including both the military operations in the Holy Land and Eastern Europe, and the Templars' financial and business dealings in Western Europe.

Dissolution

![]() In

1305, the new Pope Clement V, based in France, sent letters to both

the Templar Grand Master Jacques de Molay and the Hospitaller Grand

Master Fulk de Villaret to discuss the possibility of merging the

two Orders. Neither was amenable to the idea but Pope Clement persisted,

and in 1306 he invited both Grand Masters to France to discuss the

matter.

In

1305, the new Pope Clement V, based in France, sent letters to both

the Templar Grand Master Jacques de Molay and the Hospitaller Grand

Master Fulk de Villaret to discuss the possibility of merging the

two Orders. Neither was amenable to the idea but Pope Clement persisted,

and in 1306 he invited both Grand Masters to France to discuss the

matter.

De Molay arrived first in early 1307. Villaret was delayed for several months. While waiting, De Molay and Clement discussed charges that had been made two years prior by an ousted Templar. It was generally agreed that the charges were false but Clement sent King Philip IV of France a written request for assistance in the investigation. King Philip was already deeply in debt to the Templars from his war with the English and seized upon these rumours for his own purposes.

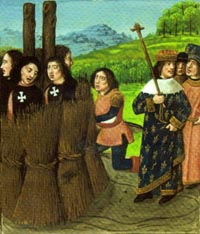

![]() Philip

began pressuring the Church to take action against the Order, as

a way of freeing himself from his debts. On Friday October 13, 1307

Philip ordered de Molay and scores of other French Templars to be

simultaneously arrested. The Templars were charged with numerous

heresies and tortured to extract false confessions. The confessions,

despite having been obtained under duress, caused a scandal in Paris.

Again under pressure from Philip, Pope Clement issued the bull Pastoralis

praeeminentiae on November 22, 1307, which instructed all Christian

monarchs throughout Europe to arrest all Templars and seize their

assets.

Philip

began pressuring the Church to take action against the Order, as

a way of freeing himself from his debts. On Friday October 13, 1307

Philip ordered de Molay and scores of other French Templars to be

simultaneously arrested. The Templars were charged with numerous

heresies and tortured to extract false confessions. The confessions,

despite having been obtained under duress, caused a scandal in Paris.

Again under pressure from Philip, Pope Clement issued the bull Pastoralis

praeeminentiae on November 22, 1307, which instructed all Christian

monarchs throughout Europe to arrest all Templars and seize their

assets.

Pope Clement called for papal hearings to determine the Templars'

guilt or innocence. Once freed of the Inquisitors' torture, many

Templars recanted their confessions. Some had sufficient legal experience

to defend themselves in the trials, but in 1310 Philip blocked this

attempt, using the earlier forced confessions to have dozens of

Templars burned at the stake in Paris.

![]() With

Philip threatening military action unless the Pope complied with

his wishes, Pope Clement agreed to disband the Order, citing the

public scandal that had been generated by the confessions. At the

Council of Vienne in 1312, he issued a series of papal bulls, including

Vox in excelso, which officially dissolved the Order, and

Ad providam, which turned over most Templar assets to the

Hospitallers.

With

Philip threatening military action unless the Pope complied with

his wishes, Pope Clement agreed to disband the Order, citing the

public scandal that had been generated by the confessions. At the

Council of Vienne in 1312, he issued a series of papal bulls, including

Vox in excelso, which officially dissolved the Order, and

Ad providam, which turned over most Templar assets to the

Hospitallers.

The elderly Grand Master Jacques de Molay, had confessed under

torture, but retracted his confession. Geoffrey de Charney, Preceptor

of Normandy, followed de Molay's example, and insisted on his innocence.

Both men were declared guilty of being relapsed heretics, and they

were sentenced to burn alive at the stake in Paris on March 18,

1314.

![]() According

to legend, he called out from the flames that both Pope Clement

and King Philip would soon meet him before God. Pope Clement died

a month later, and King Philip died in a hunting accident within

the year.

According

to legend, he called out from the flames that both Pope Clement

and King Philip would soon meet him before God. Pope Clement died

a month later, and King Philip died in a hunting accident within

the year.

With the Order's leaders killed, remaining Templars around Europe were either arrested and tried under the Papal investigation, absorbed into other monastic military orders, or pensioned off and allowed to live out their days peacefully. Some may have fled to other territories outside Papal control, such as Scotland (then under excommunication) or to Switzerland. Templar organisations in Portugal escaped lightly through the imaginative expedient of changing their name from Knights Templar to Knights of Christ.

In 2001, a document known as the "Chinon Parchment" was

found in the Vatican Secret Archives, supposedly after having been

![]() misfiled

in 1628. It is a record of the trial of the Templars, and shows

that Clement absolved the Templars of all heresies in 1308, before

formally disbanding the Order in 1312. (In October 2007, the Scrinium

publishing house published secret documents about the trial of the

Knights Templar, including the Chinon Parchment.)

misfiled

in 1628. It is a record of the trial of the Templars, and shows

that Clement absolved the Templars of all heresies in 1308, before

formally disbanding the Order in 1312. (In October 2007, the Scrinium

publishing house published secret documents about the trial of the

Knights Templar, including the Chinon Parchment.)

![]() It

is now the Roman Catholic Church's position that the medieval persecution

of the Knights Templar was unjust; that there was nothing inherently

wrong with the Order or its Rule; and that Pope Clement was pressured

into his actions by the magnitude of the public scandal and the

dominating influence of King Philip IV. As on other occasions, it

has not expressed an opinion as to how the highest moral authority

on earth could have colluded in the torture and killing of innocent

men.

It

is now the Roman Catholic Church's position that the medieval persecution

of the Knights Templar was unjust; that there was nothing inherently

wrong with the Order or its Rule; and that Pope Clement was pressured

into his actions by the magnitude of the public scandal and the

dominating influence of King Philip IV. As on other occasions, it

has not expressed an opinion as to how the highest moral authority

on earth could have colluded in the torture and killing of innocent

men.

Legacy

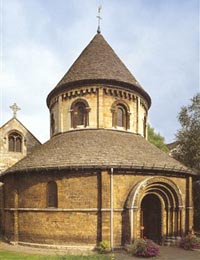

![]() With

their military mission and extensive financial resources, the Knights

Templar funded a large number of building projects around Europe

and the Holy Land. Many of these structures are still standing.

Many sites also maintain the name "Temple". For example,

some of the Templars' lands in London were later rented to lawyers.

Two of the four Inns of Court are the Inner Temple and Middle Temple,

which led to the names of the Temple Bar gateway and later the Temple

tube station.

With

their military mission and extensive financial resources, the Knights

Templar funded a large number of building projects around Europe

and the Holy Land. Many of these structures are still standing.

Many sites also maintain the name "Temple". For example,

some of the Templars' lands in London were later rented to lawyers.

Two of the four Inns of Court are the Inner Temple and Middle Temple,

which led to the names of the Temple Bar gateway and later the Temple

tube station.

Distinctive architectural elements of Templar buildings include the use of the image of "two knights on a single horse", representing the Knights' poverty, and round buildings designed to resemble the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

The story of the secretive and powerful medieval Templars, especially their persecution and sudden dissolution, has been a tempting source for many other groups which use alleged connections with the Templars as a way of enhancing their own image and mystery.

At least the 1700s the York Rite of Freemasonry has incorporated some Templar symbols and rituals, and have a modern degree called "the Order of the Temple". The Sovereign Military Order of the Temple of Jerusalem, founded in 1804, has achieved United Nations NGO status as a charitable organisation

|

|

The Knights Templar have become associated with legends concerning

secrets and mysteries handed down to the select from ancient times.

Rumours circulated even during the time of the Templars themselves.

Freemasonic writers added their own speculations in the 19th century,

and further fictional embellishments have been added in modern movies

such as National Treasure and Kingdom of Heaven, best-selling novels

such as Ivanhoe and The Da Vinci Code, and video games such as Hellgate:

London and Broken Sword: The Shadow of the Templars.

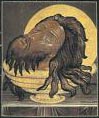

Many Templar legends are connected with the Order's early occupation

of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, and speculation about what relics

the Templars may have found there, such as the Holy

Grail or the Ark

of the Covenant. That the Templars were in possession of some

relics is certain. Many churches still display relics such as the

bones of a saint, a scrap of cloth once worn by a holy man, or the

skull of a martyr: the Templars did the same. They were documented

as having a piece of the True Cross, which the Bishop of Acre carried

into battle at the disastrous Horns of Hattin. Saladin captured

the relic, which was then ransomed back to the Crusaders when the

Muslims surrendered the city of Acre in 1191. They also possessed

the head of Saint Euphemia of Chalcedon. The subject of relics also

came up during the Inquisition of the Templars, as several trial

documents refer to the worship of an idol of some type, referred

to in some cases as a cat, a bearded head, or in some cases as Baphomet,

according to one theory a French misspelling of the name Mahomet

(Muhammad).

![]() Idol

worship was included in the charges brought against the Templars

leading to their arrest in the early fourteenth century. This accusation

of idol worship levied against the Templars has also led to the

modern belief by some that the Templars practised witchcraft.

Idol

worship was included in the charges brought against the Templars

leading to their arrest in the early fourteenth century. This accusation

of idol worship levied against the Templars has also led to the

modern belief by some that the Templars practised witchcraft.

There was particular interest during the Crusader era in the Holy Grail myth, which was quickly associated with the Templars, even in the 12th century. The first Grail romance, the fantasy story Le Conte du Graal, was written in 1180 by Chrétien de Troyes, who came from the same area where the Council of Troyes had officially sanctioned the Templars' Order. In Arthurian legend, the hero of the Grail quest, Sir Galahad (a 13th-century literary invention of monks from St. Bernard's Cistercian Order), was depicted bearing a shield with the cross of Saint George, similar to the Templars' insignia. In a chivalric epic of the period, Parzival, Wolfram von Eschenbach refers to Templars guarding the Grail Kingdom. A legend developed that, since the Templars had their headquarters at the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, they must have excavated in search of relics, found the Holy Grail, and then proceeded to keep it in secret and guard it with their lives. However, in the extensive documents of the Templar inquisition there was never any mention of anything like a Grail relic, let alone its possession by the Templars.

One legendary artefact that does have some connection with the Templars is the Shroud of Turin. In 1357, the shroud was first publicly displayed by the family of the grandson of Geoffrey de Charney, the Templar who had been burned at the stake with Jacques de Molay in 1314. The artefact's origins are still a matter of controversy. In 1988, a carbon dating analysis concluded that the shroud was made between 1260 and 1390, a span that includes the last half-century of the Templars.

There is a popular idea that the Knights Templar were sympathetic to the Cathars and allied with forces loyal to the Counts of Toulouse. The evidence is that the Templars were not sympathetic to the Cathars - in fact the evidence that any sympathy from the military orders came from the Knights Hospitaler.

If you want to learn more about these questions from experts like Henry Lincoln, on location in the Languedoc, you might be interested in Templar Quest Tours.

Recommended Books

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Templar Goods

Templar DVDs

|

| |

|

|

|

|